Having been a radio operator-scout during the Great Patriotic War, the Sevastopol native acquired his ‘home’ in Belarus. In addition, for a long time, before he died, he was its `main peacemaker`. In 2001, the veteran was awarded the Order of Francysk Skaryna for special merits; in 2008, he was given the Order of Honour; and Cambridge University called Yegorov an `Outstanding figure of the 20th century`, naming him among the world’s most outstanding intellectuals.

I have audiophiles of his voice in my journalistic archive, which I listened to while preparing an article on Marat Yegorov for the 65th anniversary of Victory, for Golas Radzimy newspaper (War and Peace of Marat Yegorov, May 14th, 2010). In the same year, on November 29th, the veteran died. His daughter Tatiana later said that his death was unexpected and came quickly. Many soldiers died in this manner during the war of course.

Journalists called Yegorov the `main peacemaker of Belarus`; for more than 40 years, he headed the Belarusian Fund of Peace. We talked to him, aged 87, on March 9th, in 2010, at the office of the Fund, in Minsk’s Trinity Suburbs. The office was filled with books, folders and souvenirs from around the world. He was distracted by calls, urgent matters and people calling on him, but he managed to concentrate and return to our conversation.

Capturing the nuances of our conversation was no easy task for a newspaper publication. His memoirs revealed all that he experienced, including lessons on war and peace-making, learnt first-hand. Alas, few veterans remain alive and those living are very old.

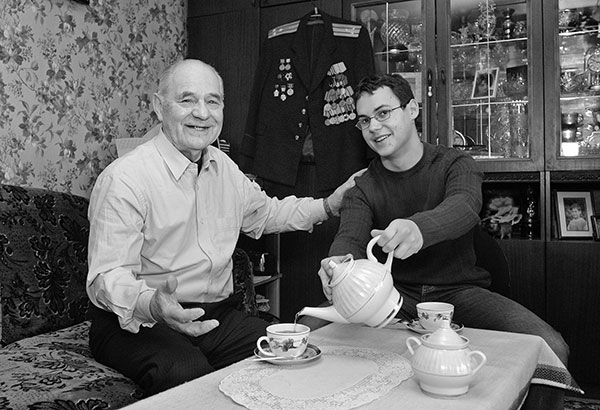

Marat Fiodorovich has full understanding with his grandson Egor. Photo Tatiana Egorova

In the early 1990s, in the Soviet Union, wartime events were marginalised, with Vasil Bykov and Ales Adamovich having difficulty being published, due to censorial editing. Wishing to fully inform readers about the cruel truth of war, Adamovich and his friends, writer-veterans Yanka Bryl and Vladimir Kolesnik, began writing documentary prose. They travelled across Belarus and, together, wrote a book entitled I Am from a Fiery Village, telling of those few who survived the burning of their Belarusian villages.

Later, Adamovich witnessed the Siege of Leningrad and persuaded St. Petersburg writer Daniil Granin to co-author Siege Book. They interviewed hundreds of witnesses, as I wrote about in Vyprabavanne Praudai newspaper (Test of Truth); the article was called Golas Radzimy and published on August 4th, 2015. As Marshal Zhukov once noticed, the truth of war is often misrepresented.

At the age of 87 Marat Yegorov was quite fit

Listening to a veteran’s recorded voice telling of his experiences can be more valuable than reading the analysis of a journalist. However, in 1970, working on Siege Book, Adamovich regretted that survivors of the siege had already forgotten much. Having only chatted briefly with Marat Yegorov, I had to find other facts through research.

Marat Fiodorovich, your peace-making work has allowed you to meet many well-known people. Which left the biggest impression?

Many did so, including one of my friends, writer Boris Polevoy: the author of ‘Story of a Real Man’. He headed the Soviet Fund of Peace from 1969 until he died, in 1981. Then, in 1982, Anatoly Karpov took his place. The many times world chess champion once admitted that he considers me his spiritual counsellor. He now heads the International Association of Funds of Peace.

We served with General Valentin Varennikov, a Hero of the Soviet Union, in his regiment: he was a battery commander and senior lieutenant, while I was a senior sergeant and radio operator-scout. Signalmen are called the army`s elite, since communication is essential at the Front. I also served with the intelligence service, so was a `person who could do everything`.

I have a book signed by the former (last) Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the USSR, General Vladimir Lobov. He wrote: `For Dear Marat Fedorovich, as a keepsake. This it will be, for ever, and for nobody, except Marat!`

While at the Front, I had to do `unreal things`.

Writers Ivan Melezh and Ivan Shamyakin are among your friends. How did you meet?

After the war, I served in Bobruisk. When Ivan Shamyakin`s ‘Glybokaya Plyn’ was published, I read it and I liked it. He wasn’t well-known at the time, only later becoming a laureate of the State Award of the USSR, a Hero of Social Labour, and an Academic. I organised a conference on the novel for my unit and we invited Shamyakin to speak. His conversation was interesting.

I was transferred to the reserve and began working in TV, having my `Topical Screen` programme in the 1970s. One episode was about the Union of Writers and I happened to see Melezh and Shamyakin in the audience. Shamyakin approached me afterwards and said that my face looked familiar so I reminded him of our meeting in Bobruisk. Then, he said to Melezh, "Ivan, we’ve found our new Head of Literary Fiction. He’s already engaged in this line of work and knows the business."

I told a few amusing anecdotes and the two Ivans asked me to work with them. I thought how interesting they were and good examples to follow, so I started working with them. We spent a great deal of time together. I organised the USSR Children`s Literature Weeks in Belarus and, when we celebrated the 90th anniversary of the birth of Yanka Kupala and Yakub Kolas, in 1972, I organised everything. This allowed me to meet many writers from across the USSR.

From the Union of Writers you moved to peacemakers...

Yes, I went to the Soviet Peace Fund. I remember that, on March 27th, the Second All-Belarusian Conference of Defenders of the Peace met at the Palace of Trade Unions. Ivan Melezh delivered a report, being Chairman of the Peace Protection Committee. Ivan Shamyakin and other worthy people were in the Presidium; we held elections and Melezh was again elected Chairman.

The Soviet Peace Fund was formed in Moscow, collecting money for peace-making activities, and the Belarusian Commission of Assistance to the Soviet Peace Fund was created at the conference. Its Chairman was People`s Artiste of the USSR Zair Azgur and Melezh suggested me as Vice-chair. Thus, I began dealing with peace issues. Soon, it will have been 40 years since I began in this sphere! I went to Moscow to learn how to carry out my work. I adopted Ukrainian experience, as peace-making was organised better in Crimea and it inspired me. Crimea is my native land, as I come from Sevastopol, from Korabelnaya Storona; my street is near Ushakova Balka. However, after some time, we left Sevastopol.

While we are on the subject of where you come from, could you tell me about your name?

My communist-mother, an elementary classroom teacher, gave me the name Marat in honour of Jean-Paul Marat: one of the leaders of the French Revolution. I was born in 1923.

Before the war, she was sent to work in Baidary [after 1945, called Orlinoye] near Sevastopol, on the way to Foros. There were few Russians; basically they were Tatars. The children sat in one classroom, and mum taught them `according to the required level of knowledge`. At that time, I was 5 years old, so I listened and grasped everything easily. Then, mum was sent to MTS near Kerch; she knew technology well, as she’d worked as a mechanic. She taught tractor operators about engines and how a tractor was made. Sometimes, when mum went out, I explained the same to cadets.

When did the war begin for you?

I went into the army on August 1st, 1941. My company comprised Georgians, Armenians, Tatars and Russians. There were no divisions by nationality. All aspired to be the ‘best’ rifleman in the Voroshilov Regiment. We passed our RWD `Ready to Work and Defend` tests and, when the war began, we persuaded the Commissioner of Military Registration and the enlistment office to take us into the army.

We were told that, come August, we’d be accepted as volunteers. They sent ten of us to school, to study. We led a healthy lifestyle, not smoking or drinking alcohol. We were good guys. We started seeing ourselves as soldiers so, before going to the Front, we decided to drink some alcohol. Senior Kostya suggested that we take half a glass of wine. We did as he said; then, we smoked a little. We agreed that we wouldn’t drink or smoke during the war but would on our return.

Did you manage to do so?

To tell the truth, I never drank alcohol during the war. All the tobacco and vodka I was given I gave to soldier friends. I helped liberate Odessa, and other cities across Ukraine, as well as Poland, Moldova, and the Caucasus. I was wounded near Warsaw. I never fought in Germany though.

I took part in the 1945 Victory Parade, in Moscow. I was to receive the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, as I’d forced a path over the Vistula with a submachine gun, with the help of a portable radio transmitter. I answered artillery fire and aided a successful crossing.

I described those events in `Order of Life`, which was published. After the war, I returned home. It was not possible to inform my mother in advance so I just walked up the stairs, meeting her as she was going down, to work. She didn’t recognise me though: the son who’d survived the war. She asked who I was calling on and I said with a smile, “You, Tatiana Valentinovna…” Such was our meeting.

My brother Vladlen died after the war and, of those ten guys, only I survived. I went to Primorski Avenue, where we always gathered, near the Monument to lost ships. It was our special place. I filled ten half-glasses and lit ten cigarettes, giving a toast to Victory on their behalf. It seemed that I heard the voice of Captain Kostya, from 1941, saying, "When we return, we’ll drink and smoke!" They did not return so I raised my glass and said, “Henceforth and forever, in memory of fallen friends...”

There is a Monument to lost ships and I am a monument to fallen friends: a living monument. Since then, whatever the situation, I’ve chosen not to drink. It is especially difficult in this position, as there are so many dinners and gatherings when people toast to peace and friendship. I lift a glass, but avoid drinking: I’m an inventor by nature so I’ve created a whole system of protection. If, at a restaurant, a waiter brings two bottles, I will have prepared one of them. If not, then water is always to hand: if vodka enters my mouth, I take a glass of water next and spit it out there. Then, I change the water. Thanks to God, I turned 87 in February, and I remain in the ranks. I don’t yet feel old age.

And you don’t take any pills?

Absolutely not! I like to walk. I buy honey from a local beekeeper: 5 or 6 3l jars annually year. My daughter Tatiana also eats honey.

My journalistic genes were transferred to her. My granddaughter, also Tatiana, studies at an American university while my younger daughter Irina has a Ph.D. in Engineering Science. She has 15 inventions and has worked as chair at the Technological University. When the USSR collapsed, she moved to Gosstroy, working for other state structures. She studied and then joined the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, working at embassies abroad as economic adviser.

My grandson Yegor, Irina`s son, was baptised by the Philaret. Yegor Yegorov graduated from the Institute of Modern Knowledge as a programmer. I’m also a technician, having grasped mathematics, physics and chemistry easily, since learning about `mum`s tractor`. However, I became a political worker, spending 27 years in the army and 38 years with the Peace Fund.

Daughters, a granddaughter and a grandson... What other legacy do you leave?

Brochures. 1986 was the UN World Year of Peace so every nation prepared materials. I introduced information on Belarus and Minsk, for which the capital received the title `Minsk: Envoy of Peace of the United Nations`. The Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the USSR then asked me to write a book `Belarus in the Fight for Peace`. It was translated into French, Spanish and English, and exhibited at the United Nations` headquarters. I was delighted.

By the way, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs views Peace Fund staff as an unofficial extension of their own ministry, since we can do what official diplomacy sometimes cannot. There may be a conference on the protection of peace in New York, to which our ambassador has no automatic invitation. However, as a private citizen of Belarus, I may attend, and have him accompany me. Since 1995, I’ve held the title of Ambassador of Peace: awarded by the World Federation of Peace. Our former Ambassador to the USA, Mikhail Khvostov, [2003-2009] also received the title.

At which large foreign forums have you spoken?

I am a member of the presidium of the European Forum of Peace. In 2005, I was invited to the Berlin headquarters to take part in a session marking the 60th anniversary of the Victory. Nearly 40 people gathered, but I was the only veteran, so was asked to deliver a speech! There were no restrictions on what I might say.

I then gave a telephone interview to ‘Junge Welt’ newspaper and was asked to speak at Berlin’s Humboldt University, at a public meeting devoted to the anniversary of the liberation of Germany from Fascism. I was anxious the night before, feeling as if I was going ‘into battle’. I outlined a plan, including statistics and names, and spoke for 30 minutes. It was one of the most difficult speeches of my life. I always speak without papers. They applauded me nearly 10 times. I began by saying that I represented all Soviet people and soldier-victors. That we came not as invaders, but as victors, and that the first action we took in the city of destroyed, burnt Berlin was to help simple people who were hungry and poor. We made porridge, opening mobile kitchens in the squares.

People were scared by Goebbels’ propaganda, believing that we might wish to poison them, so our cooks had to eat from the bowls themselves to convince people. Children were the first to approach, taking their scoops. In my speech, I said that they were young envoys of peace: the future of Germany: People`s diplomats. A woman then stood up and said, "I was one of those children".

I finished with words by Nâzım Hikmet, the Turkish poet and fighter for peace: `If I will not shine, / If you will not shine, / If we will not shine-/Then who will disperse darkness?`

I saw the interpreter`s tears as she translated.

I know that you have interesting joint programmes with Germans...

Yes, I have. In particular, in 2001, we held our Flight of Peace, devoted to the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the Great Patriotic War and the 15th anniversary of Chernobyl. We went by bus from Minsk to Brest, then across Poland to Germany. We planted Trees of Peace from Minsk’s Khatyn. It was April and nature was awakening. A cameraman joined us, helping us make a good film. I spoke at each place and was told that, although I’d given 15 speeches, I never repeated myself. We’d drive into a city and see children on tricycles surrounding us, welcoming us by ringing their bells. It was wonderful!

Whom among the Germans co-ordinated the project?

Johannes Thiele, who worked with us on helping children from Chernobyl-affected regions. He brought humanitarian supplies and helped with arrangements for restorative trips. He used to teach at a college but then devoted himself to peace-making activities.

His father was killed near Vitebsk, by partisans. I received a call from workers in Vitebsk telling me that a German was looking for the burial place of his father, so I asked them to help him. They located it in one of the regions and told him that I’d facilitated, so we later met.

Johannes is from the city of Korschenbroich, in Düsseldorf District. He told me, “My heart is heavy as I know that many people from Belarus died, I feel responsibility for my father’s actions.” He added that his father had been kind, and had never even fired a shot. I suggested that we should think of a plan and we came up with the idea of ‘Chernobyl’ children going to Germany for their health.

I’d taken 216 Jewish children from Gomel Region to Israel previously, and had worked with my former comrade in arms, General Varennikov, to take 1,000 Belarusian children from Chernobyl-affected regions to military sanatoria in the USSR.

Can you tell us more about your time at the Front with the future general?

Varennikov took my letter of request to the Minister of Defence, Yazov, for signing. I reminded Varennikov that he ‘owed me’ from our time crossing the rivers of the Southern Bug, Inhul and Inhulets, fighting with the 8th Guard (after the capture of Dnepropetrovsk, it became the 3rd Ukrainian Front). We were going to Odessa, forging rivers ahead of the transport unit. We had to deliver shells for tanks and the artillery, carrying them about our necks. I carried a 25kg radio, in addition to two mines, a submachine gun and accumulator batteries: 50kg in all!

I sometimes say to the young that, if they want to feel some aspect of the war, they should carry a sack of potatoes on their shoulders and walk for 30 or 40km, as we used to do. We’d navigate ravines and hills. I’d often be told to run ahead and see what lays beyond a hill, so I did.

There was one occasion when I scouted beyond a couple of hills and found four vehicles, loaded with boxes of mortar bombs. The Germans` gun tube was 81mm, while ours was 82, so their shells were suitable for ours. I decided to take a vehicle, since there were no Fascists around and I knew how to drive, having learnt at military training school. However, the car was French, a `Renault`, and I had trouble getting it started. Meanwhile, the Germans returned and began shooting in my vicinity. I was surprised, as their attack could have blown the mortars sky-high and them also. They tried to bully me rather than making a direct hit. Luckily, I worked out the gear-box and drove away, taking twists and turns to avoid being hit by enemy fire. I was heading for our soldiers, followed by a German tank. There was so much firing it was like an orchestra playing!

Our men realised there was an enemy vehicle coming and were ready to go on the offensive but I flashed the sun with a mirror. Varennikov saw it and realised that it must be me! He called off our men from shooting at me and, rather, they managed to put the tank following me out of action. They all received awards as a result: I helped the future general receive his Order! A few days later, I hijacked a second vehicle and captured two drivers, for which I was awarded the Red Star order. Varennikov knew me well. After Vistula, I also helped draw fire for him.

Later, when I presented my request to him, I reminded him that he ‘owed me’, because of the Order he’d received. He couldn’t remember at first, wondering if we’d played a card game. He was the Deputy Minister of Defence and Commander-in-chief of the land forces of the USSR by that time. He started laughing, remembering what had happened. He took then my letter to the Minister of Defence for signing. Thanks to that Fascist tank that we burnt, a thousand Belarusian children managed to go on a trip to improve their health...

By Ivan Zhdanovich