Over 3,000 artefacts found during archaeological digs at Bykhov Castle in Mogilev Region

The NAS Archaeological Scientific-Museum Exposition of Belarus (2009) magazine, prepared by historians Yury Zayats and Olga Levko, details excavations in the ancient cities of Polotsk, Drutsk (now an agro-town in Tolochin District of Vitebsk Region) and Vitebsk. They note that, for many years, the NAS Institute of History has worked with Russian colleagues, digging as far down as 11m. Vitebsk is the most studied, with excavations over territory of more than 17,000m square.

What relevance do findings have? Can objects change our view of the past? The latest Internet sensation is a publication by well-respected Israeli archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman. Looking at 70-year-old excavations, across the territories of Palestine and Egypt, they’ve concluded that no real evidence exists for the patriarchs, the Kingdom of Israel, or a mass exit from Egypt to ‘the promised land’. Their Bible Unearthed asks whether ‘the book of books’ is pure fantasy.

About five years ago, I visited Egypt and went on an excursion to Luxor (once known as Thebes). The world centre of archaeology is divided into two: ‘the City of the Living’ on the right and ‘the City of the Dead’ on the left bank of the Nile. The latter has the Valley of the Kings, where more than 40 Pharaoh tombs are located. I learnt for the first time that the well-known Egyptian pyramids were built more than 4,000 years ago not by slaves — as earlier believed — but by civilians. Egyptian experts base their theory on items found during excavations of burial places near the Pyramid of Cheops (a place they believe was forbidden to slaves). Zahi Hawass, the Director General of the Supreme Council for Antiquities, headed excavations.

Pot from the ancient Milograd settlement. Exhibit from Museum of Ancient Culture, at NAS of Belarus

Belarusian archaeologists now believe that Minsk was founded not on the modest River Svisloch but on the River Mena (Menka). An exhibition at the Institute of History shows items found in the ancient city centre, near the village of Gorodische, not far from Minsk, near to the small River Ptich. In the third display room, a photo and a plan of the ancient settlement are on show, showing the town covering an impressive 35 hectares. Ornamented sashes worn by soldiers, part of a book rivet, and an Arabian dirham from 893 are among the ancient items found there, showing the level of city culture and indicating the initial placement of Minsk on the River Mena.

This third hall contains items dating from the classical Middle Ages: the 9-13th centuries. Of course, primitive men lived in the south of Belarus prior to this time. Two years ago, we printed an article entitled ‘The Scale of History’ (#12, 2012), informed by my tour of the Archaeological Museum. I was invited by the Secretary of the Department for Humanitarian Sciences and Arts at the NAS of Belarus, Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor Alexander Kovalenya. He was rightly proud of the exhibition, created when he was the Director of the Institute of History (from October 2004). The museum opened in 2007, during the First Congress of Scientists, based on the Institute of Belarusian Cultures, which was founded in the 1930s.

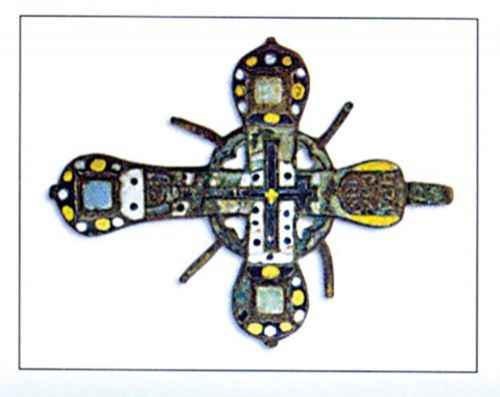

Cross. Copper, enamel. 16th century: found at Snyadin’s burial site, in Petrikov District (Gomel Region).

Digs by Oleg Iov

From dilettantism to science

The museum is divided into four sections and gives one an immediate sense of the seriousness of its task. Portraits of people, mainly archaeologists who promoted their science from the 18th century onwards, stare down from the walls. Among them is Zorian Dolenga-Khodakovsky, who was the first to receive a permit to dig. Beside him are the brothers Yevstafiy and Konstantin Tyshkevich: noble counts who founded the first private museum of antiquities in Logoisk District.

There are details of the first excavation and original archaeological diaries, from which so much can be learnt. Domestic archaeology as a science was ‘legalized’ in 1927, with the Archaeological Commission of the Institute of Belarusian Culture founded to support regional ethnographers and societies. Slides and photos from the first expeditions bring us a sense of the excitement of those early days. There is also a map of the country, labelled with the major archaeological sites: some investigations are now complete while others are ongoing.

Tile depicting Radziwill family coat of arms. Clay, glaze. 1670. Glusk Castle (Mogilev Region).

Digs by Irina Ganetskaya

“We teach students, senior and gymnasium pupils and lyceum students here,” emphasizes Alexander, indicating additional information on mobile stands. “We aim to make the exhibition educational, to teach young people about those selfless archaeologists who dedicated their lives to delving through past centuries, back to the times of mammoths. Archaeology brings understanding of how much time has passed, and how many people have lived in those centuries. It makes us appreciate what we have today all the more.”

Unfortunately, many of the first finds are now held in foreign collections or have been lost. The museum’s copy of Antiquities of Belarus in the Museums of Poland (1979) by archaeologist Leonid Pobol, details some of the items removed. The repressive years of the 1930s led to many archaeologists being exiled or executed, as the exhibition details. Later, during the Great Patriotic War, collections kept across the BSSR were taken to Germany by the Nazi invaders and many remained there after the Victory.

Luckily, on show are relics discovered by Levdansky, who was the Academic Secretary of the BSSR NAS’ Institute of History from 1931 to 1937, and who headed the Department of Archaeology, as well as those unearthed by Isaak Serbov and other colleagues.

Spur. 15th century. Oshmyanets burial site in Smorgon District (Grodno Region).

Digs by Edvard Zaikovsky

Rarities from ‘Age of Mammoths’

The second hall looks at the time of primitive Belarus: the Upper Paleolithic, Stone Age, and Bronze and Early Iron Age. There are unique prehistoric exhibits, accompanied by stories of how, who, what, where and when they were discovered. In particular, there is a tribute to Konstantin Polikarpovich who, in the 1920s and 1930s, collected data on a number of settlements from the Stone and Bronze Age across BSSR territory. He discovered, in 1927, a Paleolithic Age settlement near the village of Berdyzh (Chechersk District, in Gomel Region) on the bank of the small River Sozh.

A second site, near the village of Yurovichi in Kalinkovichi District (near Pripyat) was discovered in 1931, it was investigated for many years. A photo dating from 2006 shows the huge skull of a mammoth: sadly, not on display in the museum. The Museum of the Paleolithic Age has now opened in Yurovichi (the only such in Belarus), overseen by archaeologist Yelena Kolechits, a Doctor of Historical Sciences. The Yurievichi site is represented via photos from various angles, and excavation results.

Finger ring. Silver with gilding. Late 10th century. Izbishche burial site in Logoisk District (Minsk Region).

Digs by Valentin Kazey

Professor Kovalenya tells us, “If you’ve been to the Louvre, or the well-known museums of St. Petersburg, you’ll know that valuable exhibits are usually displayed upon velvet. In our country, we place them on sand, since this is where they were found. Just imagine, 24,500 years ago, people were living in Belarus; the date may be even earlier. We have the remains of a forest elephant, known to have grazed about 100,000 years ago but no tools have been found nearby to show human settlement. We can trace the history of pre-ice age people but physical evidence is lacking.”

In Neolithic times and the early Bronze Age, people are known to have extracted stone from near the small River Ros, not far from today’s Krasnoe Selo, in Volkovyssk District of Grodno Region. In Europe, only a handful of similar mines have been located. Vertical wells were dug to a depth of 8m, to exploit calcareous deposits of flint, found in horizontal drifts. The flint was then used to make tools, alongside horn and bone. Archaeologist Andrey Voitsekhovich explains that tools made from the horns of deer have been found nearby.

The monument of the Middle Dnieper culture is an impressive site, revealing a Bronze Age settlement and burial ground. A sandy stylized tomb has brought forth ceramic pots: one with a rounded base and another with a flat bottom. Archaeologist Nikolay Krivaltsevich found them near the village of Prorva (Rogachev District, Gomel Region) and believes that they are evidence of the ancient custom of cremating the dead and placing them in funeral urns. The pots were all found ‘upside-down’, indicating the ‘end of life’.

Iron axe from 13th century burial. Oshmyanets burial site in the Smorgon District (Grodno Region). Digs by Edvard Zaikovsky

Each exhibit inspires reflection. Prof. Kovalenya tells us, “Some exhibitions have only one object, placed in its own square metre, but we take a different approach, choosing to show how objects were used and how society developed. We discovered an ancient workshop, where stone items were carved. Skilled experts would have worked there, who knew their trade well and earned a good ‘living’. Hunting was common with flint arrowheads and fishing hooks — even some very large ones, showing the size of the fish!”

Archaeologists take a global approach in their analysis. Maxim Chernyavsky has seen success on the Belarusian peatbog sites of Krivino and Osovets (Beshenkovichi District, Vitebsk Region), finding a bear’s bone and a shovel using flint, as well as the tip of a javelin or arrow. Such finds tell us so much! The sites are referred to as North-Belarusian cultures, dating from the last quarter of the 3rd century or the mid-2nd BC. “Osovets is Belarus’ most unique Neolithic / Bronze Age site,” explains Andrey Voitsekhovich. “The peat layers are perfect for preserving organic matter.”

Amulets have been found, as well as various articles from amber, timber and bone. Colleagues have been digging successfully for nearly 15 years, unearthing some items now stored at the National Art Museum. There have been images of animals, including those with human faces, and a huge auroch horn (found at a primeval site in Beshenkovichi District).

Temple ring and mounts from forehead ornaments. Non-ferrous metal. Malevichi burial site in Vileika District (Minsk Region).

Digs by Lyudmila Duchits

When the Museum of Nature at the Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park developed a new concept, artist Peter Lobkovich took the horn to ‘restore’ the animal — thought to be a black auroch — with its enormous skull. Aurochs are related to bison and were driven almost to extinction by man’s hunting. Using the horn as the centrepiece, the Pushcha museum now has a whole scene depicting an ancient hunt.

Belarusian territory: the ancestral home of Slavonic people?

Only a few Iron Age sites have been found on our land but we have enough to learn a great deal about their way of life, customs and culture. The settlements date from the second half of the first millennium B.C. According to guides, the earliest artefacts are Scythian. Meanwhile, Milograd culture, dating from the 9th century B.C. to the 1st century A.D., is the earliest known on Belarusian territory. It expanded across the Pripyat, as we know from finding arrowheads and earrings in the form of Scythian circles. A well-known clay figure of a horse was found during digs in Goroshkov (Rechitsa District, Gomel Region) which inspired writer Vladimir Lipsky to create his story entitled Milogarad Horse. That small horse is now stored at the Archaeological Museum of Gomel State University (named after Frantsisk Skorina).

Students Maria Ivankovich and Roman Golynsky worked on archaeological digs at Bykhov Castle

“In the north of Belarus, in the Iron age, engraved ceramics were common, made by the ancestors of modern Lithuanians: Scythians and Balts influenced the formation of Belarus,” notes Prof. Kovalenya. Foreign historians are impressed by such evidence of cultural ‘collisions’, showing how various people influenced one another, with Belarus at the centre of this interchange: a geopolitical and geo-cultural fracture between East and West, North and South.

We have finds from settlements along the Rivers Dnieper and Dvina, which belonged to the ancestors of modern Latvians. Some date from the turn of the first millennia, found in the south of Belarus, where the Roman Empire had strong influence at that time. In Polesie, archaeologists have found Roman imported fibulas, beads, and high-quality ceramics (which differ from those found elsewhere). In Loev District of Dnieper Region, finds are similar to those discovered in Western Europe.

Bear’s shoulder bone with fragments of a silicic arrow and an auroch’s horn. Asavets II settlement

in Beshenkovichi District (Vitebsk Region). Late Neolithic and Bronze ages. Digs by Maxim Chernyavsky

The museum displays a copy of a map by historian Herodotus, who spoke about the sea in Polesie (probably referring to the flood plains of Spring). In Brest Region, archaeologists have found traces of Goths: North-German tribes moving from Scandinavia to the Northern Black Sea Coast. The Wielbark culture is also represented in the displays. Tribes migrated from the north of Poland, partially settling in Brest Region.

Artefacts show the influence of Kiev, Prague and Kolochinskaya, Slavs and Early Slavs. Prof. Kovalenya notes that expert opinion now seems to agree that Slavs appeared in our territory from between the Pripyat and Ptich rivers. He adds, “Of course, hypotheses differ but we have concrete finds.” As to whether Slavs were related those of Indian origin, he answers, “We have material evidence of this but are still pondering from whence the early Slavs appeared. We’ve found solar signs used by the Slavs, with the swastika [the Hindu symbol of peace]. The territory of Belarus can be considered as an ancestral home of the Slavic people, although this still requires scientific substantiation. Half of modern Belarus is covered by forest and, at that time, forest covered 90 percent of the land. There were no roads, so people settled on the banks of rivers and lakes. It’s vital to share research on the Latvians, the Lithuanians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Russian and Poles, combining our knowledge to better comprehend the past.”

Many volunteers took part in digs near Grodno

It’s impossible to enumerate every interesting exhibit at the Archaeological Museum, since each deserves its own article. New finds are still being made and students and teachers are able to learn from what has been discovered, joining curators for special lessons. Prof. Kovalenya notes that training experts is difficult without genuine artefacts and a systemic representation of history. He adds that teachers base whole cycles of lessons around museum artefacts, bringing students from higher educational institutions for practical training. In fact, the museum has the richest archaeological collection in its archives, stored carefully, to protect Belarus’ historical and cultural heritage. No doubt, those who come ahead of us will thank us for our labours. As wise people say, without the past, there is no future.

By Ivan Zhdanovich