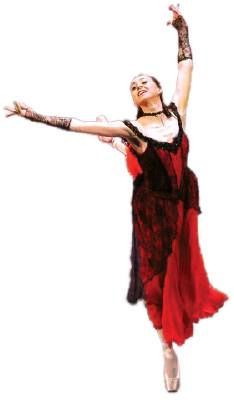

For more than 20 years, Nina Ananiashvili was the prima of the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre, constantly on tour worldwide. No modern ballerina can boast of such an international career. Ten years ago, she radically changed her life, agreeing to become the Artistic Director of the State Ballet of Georgia, where she was born and raised. Nina continued to dance, but her main work has been staging performances of the highest quality, which she is now taking on tour. Minsk will be among the first places to stage her Laurencia, this November.

Nina, why Belarus and why Laurencia?

Nina, why Belarus and why Laurencia?

I have an old friendship with Minsk, having danced here previously. In recent years, our co-operation has been renewed, with several interesting joint projects, praised by audiences and critics. The Minsk Bolshoi Theatre asked me to stage any performance and I chose ‘Laurencia’, by Vakhtang Chabukiani, the great Georgian choreographer, as it hadn’t been staged for a long time. We revived it in Georgia in 2007 but my current staging is entirely new. I was helped by well-known Georgian masters: People’s Artistes who danced in the times of Chabukiani. Certainly, we have added something of our own: transitions and mise-en-scènes.

Have you found a role for yourself?

When you stage a ballet, it’s difficult to dance in it yourself. I admit that I always dreamed of dancing in ‘Laurencia’, as it is very technical, with a lot of jumps. I was such a ballerina but, unfortunately, it was never staged in my time. To simultaneously direct and perform a leading role is very difficult.

I’ve had an absolutely different task: crafting a ballet for your Bolshoi Theatre and for your troupe. I’m anxious at the thought of Vladimir Vasiliev and Tatiana Terekhova coming to see the show (they both danced in ‘Laurencia’, in the final shows at the Mariinsky Theatre). However, it’s been my dream to return the performance to the world.

Are you afraid of criticism?

My staging is dynamic and edited down; it’s intense and compelling. We can’t recreate the original performance by Chabukiani, since it would always be merely an imitation. It’s better to transfer the heritage of the great master to today’s generation.

What do you think of our troupe?

The troupe is very good and different. The trouble is that we lack enough time and the workload is huge. We can only aspire to making every member of the cast feel involved, as if they are founding this performance. Then, it will be of the highest level.

Our troupe has no stars of international level…

You have your own stars, and the greatest estimation is to see full houses. This is often lacking, but you have these. It is impossible to deceive people: if they don’t like stagings, they won’t come. Treat them with respect and love, and appreciate them.

Why do you think the world lacks ‘big names’ in ballet these days?

I can name any theatre worldwide and you won’t remember their stars but that doesn’t mean that they don’t have any; you simply don’t know them. Plisetskaya, Maximova and Vasiliev are talents born once every hundred years. The fact is that we live in different times. Previously, there were only a few theatres, so they were recognisable all over the world. Now, every big city has its own troupe, and foreign dancers are rarely invited. Even Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre cannot boast of ‘stars’. It’s the same with rock music. The best known bands may not be known in the West or in America — although they are stars in their own country.

Most Belarusians know Alexander Vasiliev as an historian of fashion and the anchor-man for TV programme Fashionable Verdict. Did you invite him to design costumes for Laurencia?

I’ve known Alexander since childhood, as his mother, Tatiana Ilinichna, taught us acting at Moscow Choreographic College. We’d chatted but lacked any creative liaisons, apart from him making sets and costumes in the 1990s for ‘Don Quixote’, in which I danced with Alexey Fadeechev. I liked his work very much. He was living in France, making costumes for various theatres, when I became the Artistic Director of the State Ballet of Georgia. I invited him to help us, including working on ‘Laurencia’. He has created absolutely original costumes for the Minsk staging.

You’ve managed the Georgian Ballet for ten years. Do you ever have regrets at having retired from dancing when you were at the peak of your international career?

I promised to help the Georgian Ballet regain its former glory, so I have fully dedicated myself to this. It’s been a challenge, but not in vain. We have a good repertoire, and western choreographers visit us, making offers for collaboration.

Nina, is your daughter following in your ballet footsteps?

No. Unfortunately or fortunately, she isn’t a ballet dancer. She is 9 years old, and keen on music and horse riding.

You did not insist?

Yelena is a big girl, like her father, so her figure isn’t right for professional ballet. Such dancing can be useful as a hobby but making it your career is another matter.

Do you wish to teach, passing to others what you received from Zolotova and Struchkova?

Everything that I know and can, I’ll pass to my pupils. Unlike Zolotova and Struchkova, I’m not in a position to focus my attention on just one or two dancers. As Artistic Director, I must think of the whole troupe. I do hope to have my own pupils one day, taking girls from a young age and raising them to the highest level, building them as Raisa Stepanovna did.

What is your secret of success?

Fate plays its part. By the time I finished school, I had won two competitions, so I was in the public eye. However, I am not from Moscow. I was a newcomer, without hope of special attention, but was lucky to be taken in by a remarkable teacher, Natalia Zolotova, who transferred me into the hands of Raisa Stepanovna.

Fate plays its part. By the time I finished school, I had won two competitions, so I was in the public eye. However, I am not from Moscow. I was a newcomer, without hope of special attention, but was lucky to be taken in by a remarkable teacher, Natalia Zolotova, who transferred me into the hands of Raisa Stepanovna.

When I came to the Bolshoi Theatre, I joined a constellation featuring Maya Plisetskaya and Yekaterina Maximova. Certainly, I had talent, thanks to my parents, but it was hard to stand out. The teacher always said, “Physical abilities you received from your parents, but you need to work yourself!” I worked!

Struchkova was a teacher sent from God. She never cared what time it was: if a dance studio was free at 10pm, that’s when she came and worked with me. When I was rehearsing `Romeo and Juliet`, she even came with a broken leg, on crutches! Few such people exist in the world. I called her my Russian mum.

Zolotova and Struchkova were always on friendly terms, with Raisa Stepanovna calling to invite them to watch me. She’d say: `Natasha, come see your Nina` — and Natalia Viktorovna would always see my performances.

Do you ever feel constrained by the Georgian Theatre?

For the first three years in Tbilisi, I helped build a wonderful repertoire, staging 27 performances. Now, we have 54. The theatre is undergoing repairs now, so we need to wait and be patient. I don’t feel constrained, as we welcome Japanese, British and Spanish dancers.

How does your husband feel about your nomadic life?

I was lucky to meet someone who fell in love not only with me, but with my profession. The ballet world places a great strain on marriages and some husbands never see their wife dance. My husband sees every one of my performances and understands every detail, despite being a diplomat and lawyer by profession. He has helped me to draw up contracts, so that our artistes enjoy the same terms as those in the West. We have convinced our actors that they need to maintain the reputation of the theatre, so that they are valued and receive honour. My husband has helped greatly with this. My career success would have been impossible without his support.