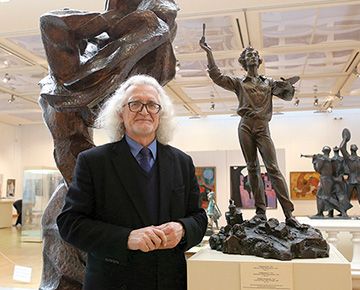

Museums tend to be quiet places, since we are often struck silent in the presence of beauty or on beholding items of great age and significance. The Director of the National Art Museum of Belarus, Vladimir Prokoptsov, has some modern ideas about how to run museums and, last year, was delighted to see his staff receive the prestigious ‘For Spiritual Revival’ Award.

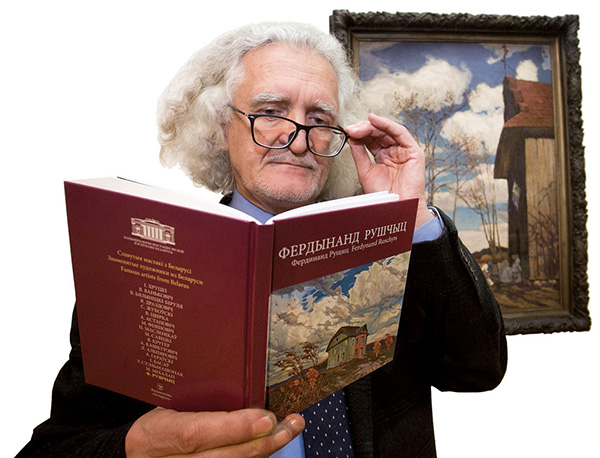

The release of a whole series of books about famous artists of Belarus is a project by the National Art Museum with direct participation of its Director, Vladimir Prokoptsov

Mr. Prokoptsov has headed the National Art Museum for several years, and has always seen large numbers of visitors through the doors (regardless of the entry fee). However, on the last Wednesday of the month, entry is without charge, and the building becomes very busy. It’s a wonderful sight to see.

The National Art Museum hosts the largest collection of Belarusian and foreign art, with about 30,000 works, forming over 20 collections. In 2015, the workers of the museum received ‘For Spiritual Revival’ award for their successful realisation of major exhibition projects, aimed at strengthening our spiritual values.

Vladimir Prokoptsov, Director General of the National Art Museum, tells us:

This award is not only an honour but bestows responsibility, obliging us to work even harder. This is the Year of Culture, so we are planning various new projects, including those with a spiritual element. We’re hosting exhibitions in Belarus, and sending collections abroad, aiming to encourage Christian values. We’ll be happy if some people find their way to church as a result. Culture is everywhere, in the home, at work and in our relationships. Culture is a gift from God, with meaning for each of us.

What is currently on display in the museum of exhibitions?

Currently on show is the ‘Goya...Picasso’ exhibition: the largest Belarusian-Spanish project in the history of modern Belarus. It features works from the Spanish Museum of Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, with exhibits on show at the National Art Museum since December. Mr. Prokoptsov gave journalists a tour, and drew attention to Vasily Pukirev’s ambiguous ‘Unequal Marriage’, created in 1875 from the 1862 original (which is stored by the State Tretyakov Gallery). The canvas is so large that figures are almost life-sized. Standing directly before the picture, you can’t help but be drawn into the scene, and feel compassion for the girl being obliged to marry an official against her will.

The Director General’s favourite exhibit is the icon of Saint Paraskeva Pyatnitsa, dated to the second half of the 16th century, and unearthed at a Belarusian church in the 1960s. Examples of ancient Belarusian art are rich and diverse. Mr. Prokoptsov also reveres a picture painted by Vilnius artist Johann Schröter, who was well-known between 1640 and 1680. One of the museum’s most mysterious works depicts both wives of Janusz Radziwiłł: beautiful Katarzyna and Maria (although one, wearing a crimson dress, was already dead by the time Janusz commissioned the work). Clearly, he wished to place both beloveds on a single canvas. Mr. Prokoptsov notes, “There’s a bat which lives in the museum attic, and I rather like the story that, at midnight, it turns into a girl who walks the halls. The bat sometimes flies into the gallery, and guards have been worried that it may damage the pictures. I painted a picture showing a girl soaring through the air, alongside myself in knightly armour, and the bat, near the portrait of Katarzyna and Maria Radziwiłł. This picture from the Nesvizh collection of the Radziwiłł family is the most mystic in the museum, which is why I chose to depict it in my picture.”

Foreign guests often visit the museum

Vladimir Prokoptsov exhibited his picture on the Night of Museums, at 00:13, for just 13 minutes. “Nobody saw the picture for any longer than this. I painted it over in black and the canvas will have a new picture placed upon it,” he explained to us during our tour, in a fashion most intriguing. He promised to tell us later what the new picture would depict.

The extension to the National Art Museum building opened in 2006, to help offer more exhibition space, but the problem remains of course, since there are over 30,000 works of art, including sculptures. Only 4 percent can be exhibited at any one time, and there are visiting collections to put on show also.

“About ten years ago, we decided to plan a museum quarter, which was supported by the Head of State,” notes Mr. Prokoptsov. The museum complex is growing, and has taken over a former student hostel belonging to the Belarusian State University (thanks to intervention by the Ministry of Culture). The four-storey building will allow visitors to spend all day viewing exhibits, as well as spending time in the café and shop. The underground floors are being used for storage, as well as to house a book shop and café (with Wi-Fi), a few exhibition and multipurpose conference halls, a souvenir shop, bar and coffee house.

The second and third floors will display Belarusian folk art and crafts, while having an exhibition hall and workshop for interactive studies with children, as well as curator offices. The restoration centre will be located on the fourth floor and on the completed fifth, mansard floor. Security will encompass the highest technologies, and the entire building will offer Internet access, as well as audio-systems and disabled access via lifts and ramps.

The topic of small homeland occupies a special place in Vladimir Prokoptsov’s creativity

Karl Marx Street is to become a pedestrianised ‘Minsk Arbat’. Construction of the museum area should be complete by 2019-2020 (beyond the originally planned 2018). “I don’t want to be overly optimistic, rather being realistic,” Mr. Prokoptsov underlines. “By 2020, when the museum area launches fully, we’ll be able to show about 10 percent of exhibits at any one time. Of course, it’s impossible to exhibit everything simultaneously.”

The museum is currently hosting a major exhibition, entitled ‘The Life and Artistry of Bakst’, devoted to the 150th anniversary of Leon Bakst: an impressionist born in Grodno. Alongside are canvases by his contemporaries: Alexandre Benois, Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, Boris Kustodiev, Isaak Levitan, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Ferdynand Ruszczyc, Nikolay Roerich, Zinaida Serebryakova, Dmitry Stelletsky, Valentin Serov, Mikhail Vrubel, Konstantin Korovin, Stanislav Zhukovsky, and Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis.

Mr. Prokoptsov notes that most of these artists are world famous, and many are our countrymen. The exhibition introduces not simply one artist, but a whole age and movement. He feels sure that spectators will find much of interest. He adds, “Stanislav Zhukovsky is traditionally perceived as ‘a singer of noble nests’, having painted about a dozen interiors. The Bakst exhibition shows another side to Zhukovsky: his outstanding landscape painting.”

It took two years to set up the exhibition, which follows on from the ‘Ten Centuries of Art of Belarus’ project, which took place in 2014, and was the second largest to be organised by the museum and Belgazprombank. The aim was educational, since few people in Belarus seemed to know much about artists of the Parisian school beyond Chagall and Soutine. A whole galaxy of creators was born across the various regions of Belarus, and became well-known in Paris.

Mr. Prokoptsov adds that, not so long ago, our fellow countrymen Byalynitsky-Birulya, Zhukovsky, and Ruszczyc were thought to be Russian artists, having received their education in Russia. He notes, “Together with Belarus publishing house, and with support from the Ministry of Information, we’ve created a series of 19 albums called ‘Famous Artists from Belarus’. The first was issued in 2010, for the 150th anniversary of the birth of Yan Khrutsky. At first, only a few volumes were planned but we decided to keep going. It’s now an unlimited project.”

During his tour, Mr. Prokoptsov told us about long negotiations to organise an exhibition of Belarusian icons at the Vatican. From late March, the relics will be on show in Rome, under the title ‘Sacral Art of Belarus from the 17th-20th Century’. Catalogues and albums have been prepared in several languages to accompany the event.

“In this Year of Culture, with the help of the Art Museum, we plan to open many new pages of history for national art. The exhibition organised at the Vatican will be replenished this autumn, going on show in Minsk. Autumn 2017 will see another major exhibition of restored sacral art items,” Vladimir explains. He underlines, “Some icons, and arts and craft items will be left only half-restored, so that people can see the ‘before and after’ condition and gain some appreciation of the work involved in restoring masterpieces.

Restorers will receive workshops within the new National Art Museum buildings, thanks to the persistence of Mr. Prokoptsov. He’s always busy, and remains actively creative himself, finding time to paint, although he admits that he’d like more hours in the week. He explains that ‘dissatisfaction’ and ‘restlessness’ inspire him as an artist.

He tells us, “I began my postgraduate studies at the Academy of Sciences, and expanded my art horizons. Science taught me how to concentrate. Now, as the director of the museum, I don’t have time to sit painting all day long. Why do I enjoy my directorial role? I’m self-sufficient and, having had an art education myself, I can speak to any artist as an equal, even with the director of the Louvre. I feel that I’m in the right place. I like working at the museum, but I also like to paint in my studio, switching from administrative work to creativity, thinking about colours, the sky, roofs, earth, apple-trees and flowers. I love the independence this gives me and feel comfortable in my role. I like to learn from others, to see how artists work and to learn how to light works most effectively. It’s important even to know how walls should be painted.”

It’s clear that you didn’t dream about becoming a museum director. Since time is limited, has painting become more of a hobby for you now?

It’s serious work. I understand my full responsibilities. If you view yourself as an artist, you should play by the rules. If it was only my hobby, I’d paint for pleasure. But, this isn’t the case. It’s true that I don’t have time to paint all day long, having only the evenings. I work at weekends and holidays. It’s not easy to enter history as a talented artist. You need to be prolific, and not all of your works will hit the mark. As long as you create one remarkable painting annually, that can touch the soul, this is enough. You need for other artists to recognise that you have achieved professionalism. Ordinary audiences tend to be less critical. I try always to improve. I do have to wear various hats and I am in competition with colleagues. I do take time out to paint, and my works are exhibited at the Gallery of the Union of Artist, with one or two used in themed exhibitions.

Why does the style of your pictures vary?

It depends on my mood and my desire to experiment. I used to combine realism with impressionism but my recent pictures are more decorative. It probably comes with age and experience. I have a different mental outlook and ‘rhythm’ today; it’s as if I’m in a chariot and cannot stop. I give my feelings away on the canvas.

Is each work individual or do you have an enduring motif?

Of course, each picture is individual. When I paint something, I immediately come up with a name. Let’s say I intend to paint a lily, night or the dawn; first of all, I think about the philosophy of the name. To evoke mystery, you should use understatement and paint things in a manner other than realistic: clouds should be green or not at all. I steer clear of the obvious unless I’m painting a straightforward still life work. Even then, you can take various approaches, deciding whether to give your table legs and what colour to paint your apples. You can make them more red than any apple would normally be. Every artist has their own philosophy and style.

Do you court public recognition?

Of course; all artists, actors, poets and writers want to be recognised for their talent. It’s been so since man first picked up a piece of coal and began to paint on a rock, seeking admiration from his compatriots. I don’t believe artists who say they don’t desire glory; I think we’re all ambitious. Of course, by nature, artists are individualists. Although poets and artists work alone, they dream of recognition. As a museum director, I want the museum to be the best in Belarus. This is natural; were it not so, how would we ever progress? Of course, there are various types of ‘glory’; one is achieved through labour while the other is cheap. Time is a great judge.

Are works by Belarusian artists interesting to foreign audiences?

Yes; of course. In fact, the Belarusian school, especially the realist school of our older generation, is rated highly. Europe lacks such a level today. Sadly, we lack an art market to support auctions. I’d like to see something in Vitebsk, since it’s been permeated by the smell of paint since the times of Chagall and Malevich. Why do we have so many casinos and so few art galleries? We want to be a European capital and we certainly have the perfect geographical position. Our cities are well-groomed. We lack a Pavarotti but we have gorgeous artworks, so why shouldn’t we take a leading role in the art market; especially when we have such traditions?

Should a museum try to guide visitors’ taste?

It’s essential. A museum should not operate without an aim: its mission is education and teaching. It’s an educational centre. Our museum is becoming more active, branching out. An exhibition does not need to be limited to art works; it can continue its theme along various avenues, for the pleasure of children and adults. Our museum has received much funding to modernise its halls and to raise salaries, with the aim of guiding public taste. A museum must act ‘aggressively’, in the best sense, being three steps ahead — especially in our modern time of globalisation. Visitors should be enticed, through lectures and excursions. I’m convinced that museums are educational; no other purpose is needed.

In your years of directorship, have you seen modern visitors become more demanding and knowledgeable?

Of course. We have the Internet now, so people can take a virtual tour of the Tretyakov Gallery or some other museum. Modern art lovers can take a two-hour trip on a Belavia plane to Paris, to see the Mona Lisa. Nothing can surprise us now. Audiences are true gourmands of art: demanding and sophisticated. We need to be ready for this, keeping up with today’s technologies, exhibition styles, methods and staff training. It’s a global issue so I, as museum director, cannot remain idle. I keep my staff on tenterhooks — although some may dislike this. In the 1960s and 1970s, the museum was a safe harbour; now, it must earn money, as well as promoting the country’s image and organising international projects. Our visitors wish to see a Marc Chagall show or a Tretyakov Gallery exhibition. Moreover, museum staff should know foreign languages. In a word, the museum format needs expansion.

Are you ‘fighting’ for visitors?

We fight for every visitor. Only interesting exhibitions and programmes attract visitors so an ideal modern museum is a large cultural industry.

It must be difficult to manage such a ‘mechanism’?

It’s not simple; it’s a huge responsibility. The museum is our country’s ‘calling card’. I’m always telling my staff that — sooner or later — new people will replace us. The museum should not remain idle; it must work and, accordingly, I bear huge responsibility, as its head. I feel and understand all this; unsurprisingly, I’ve gone grey early!

Is a museum director a manager or an academic?

Everything together. I can hardly imagine a manager — rather than a painter or art critic — as a National Art Museum director. Can you imagine an economist heading the Hermitage or the Tretyakov Gallery? I personally cannot. Of course, these museums have their own managers but must be headed by a specialist. A museum director is a universal figure: they should be a manager, an economist and an art critic. This is why I have no shame in continuing to learn something new.

Do you suffer from a split personality: director Prokoptsov and artist Prokoptsov?

I enjoy complete harmony, as the former supplements the latter. I did experience a split personality when working for the Council of Ministers, as I seldom took part in exhibitions. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, state officials were not encouraged to display their works alongside those of artists. I feel very comfortable now.

In heading the museum, you’ve arranged many foreign shows. Do you plan to exhibit the National Art Museum’s rich collections abroad?

We have such plans and have already exhibited Khrutsky’s pictures in Vilnius — as part of celebrations of the 200th anniversary of the artist’s birth. At present, we’re working on a joint project with the Vatican, taking our Belarusian Orthodox and Catholic icons there. Of course, such events need insurance: the larger an exhibition, the more money is needed.

What is ‘true art’ for you?

It’s life. No life is possible without art. Fine arts make people spiritually wealthier, kinder and more harmonious. Some cultural values resemble behavioural norms (like letting the elderly go through a doorway first and respecting women). Why did ancient people draw on walls? Even then, they were observing the stars in the sky and were eager to reproduce them. In the morning, the stars disappeared but a handsome hunter or a scene from primeval life was painted on a wall. All these drawings are worthy of admiration. They are our heritage, with museum value.

These are Vladimir Prokoptsov’s themes and thoughts: real, imagined and tangible. No personal development is possible without them.

By Viktor Mikhailov