Exhibition of Japanese engravings from Hermitage collections held at National Art Museum

The St. Petersburg Hermitage is, of course, one of the largest museums in the world and the richest treasury of art. It is said that its storerooms house various valuable relics originating from Belarus but arranging their ‘homecoming’ is a delicate business. International practice shows that the solution of such questions is far from easy.

64 early-17th to late-19th century works by outstanding Japanese masters of engraving on show in Minsk

However, this circumstance does not prevent close co-operation between the Hermitage and our Belarusian museums, as noted by the Culture Minister of Belarus, Boris Svetlov. Speaking at the opening of the present exhibition in Minsk, he emphasised that such cultural ties — between the Hermitage and the National Art Museum of Belarus — date back to the 1960s. Minsk hosted its first exhibition of Dutch masters and 18th century works from the County of Flanders from the Hermitage in 1966. In the 1980s, two other exhibitions followed: of Western European engravings and Tibetan art.

Decades of co-operation became the basis of a corresponding agreement between the museums signed in 2012. This document, according to the Culture Minister, provides not only for exchange of exhibitions, but publishing of editions, and training of curators and restorers. “I believe that this exhibition is another step towards realising the best elements of the agreement, promoting friendly relations between our two museums,” asserts Mr. Svetlov.

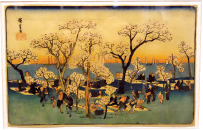

The Edo. Capital and Epoch: Japanese Engraving Ukiyo-e of the 18th-19th Centuries from the Collection of the State Hermitage exhibition features 64 works by outstanding masters, dating from the early 17th-late 19th century. Ukiyo-e is translated as ‘pictures of a changeable or floating world’ and is a major kind of xylograph in Japan. The first black-and-white images illustrated stories but engraving became an independent art form in the first half of the 17th century, when images were sold separately. Most prints were published in Edo (modern Tokyo) and were bought for pleasure, or as souvenirs. Until the mid-18th century, the prints remained monochromatic, with tints occasionally added ‘by hand’, but, gradually, extra layers were added during the printing process, to add colour; eventually, this led to fully-fledged heterochromatic prints.

The Edo. Capital and Epoch: Japanese Engraving Ukiyo-e of the 18th-19th Centuries from the Collection of the State Hermitage exhibition features 64 works by outstanding masters, dating from the early 17th-late 19th century. Ukiyo-e is translated as ‘pictures of a changeable or floating world’ and is a major kind of xylograph in Japan. The first black-and-white images illustrated stories but engraving became an independent art form in the first half of the 17th century, when images were sold separately. Most prints were published in Edo (modern Tokyo) and were bought for pleasure, or as souvenirs. Until the mid-18th century, the prints remained monochromatic, with tints occasionally added ‘by hand’, but, gradually, extra layers were added during the printing process, to add colour; eventually, this led to fully-fledged heterochromatic prints.In creating the xylographs, there were four basic participants: the publisher, who studied demand, and defined the theme; the artist, who made an outline drawing in ink and specified which colours he thought would work best; the carver, who glued the facing side of the sketch to a wooden board, and then deepened the field not filled by the drawing, keeping contours in relief; and the printer, who laid colours on the surface of the board, before spreading sheets of paper to make imprints — usually for a circulation of about 200.

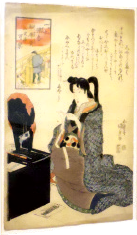

In the first decades of Ukiyo-e development, two extremely popular genres emerged: bijin-ga (prints of beauties) and yakusha-e (prints of actors). ‘Portraits’ of well-known courtesans and popular kabuki actors served as advertising or as a ‘playbill’ for theatres. Suzuki Harunobu’s ‘big style’ xylography combined the lofty poetic atmosphere of classical Japanese painting from the 9-11th century, launching a new phase for bijin-ga, elevating the art form to create a modern, urban variant.

In the first decades of Ukiyo-e development, two extremely popular genres emerged: bijin-ga (prints of beauties) and yakusha-e (prints of actors). ‘Portraits’ of well-known courtesans and popular kabuki actors served as advertising or as a ‘playbill’ for theatres. Suzuki Harunobu’s ‘big style’ xylography combined the lofty poetic atmosphere of classical Japanese painting from the 9-11th century, launching a new phase for bijin-ga, elevating the art form to create a modern, urban variant.Harunobu inspired many of his contemporaries, including Isoda Koryūsai (1735-1790) and Ippitsusai Buncho (1755-1792), as well as Katsukawa Shunshō (1726-1793) in his early works. Shunshō then moved into yakusha-e, and made no less considerable changes to theatrical engraving than his predecessor to the bijin-ga genre. Previously, the role was depicted, rather than the actor (with an inscription added to identify the player); now, actors became recognisable.

Kitagawa Utamaro (1754-1806) came to lead the bijin-ga genre, creating an idealised type of female beauty, as seen in his ōkubi-e (big heads). The accent was upon femininity and inspired a new wave of artists through the last decades of the 18th century and into the early-19th: the Golden Age of Ukiyo-e.

Throughout the period of Edo (1603-1868), the Japanese government enjoyed major political and economic reform three times, aiming to reinforce forgotten Confucian virtues. Indulging in luxuries became frowned upon, and brought restrictions upon printing, with engravings censored for content.

Throughout the period of Edo (1603-1868), the Japanese government enjoyed major political and economic reform three times, aiming to reinforce forgotten Confucian virtues. Indulging in luxuries became frowned upon, and brought restrictions upon printing, with engravings censored for content.Images of military clans from the 16th century and beyond were banned, as was the inclusion of names of sumo wrestlers, kabuki theatre actors and courtesans (except for girls from the cheerful Edo Quarter). Such restrictions upon bijin-ga and yakusha-e inspired the development of other genres: landscapes and military-historical engravings, known as musha-e.

The most well-known landscape artists of Ukiyo-e are, undoubtedly, Katsushika Hokusai (1760/?/-1849) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), who depicted recognisable locations to correct scale (unlike classical paintings of the past). Both artists published several series devoted to landmark sites of the capital, conveying the atmosphere of the city and its residents: their cares, holidays and everyday life.

In the 19th century, Utagawa school came to the fore, nurturing two outstanding masters: Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861). Both led in the genres of yakusha-e and musha-e. Kunisada began as an artist of bijin-ga, but later created sketches for theatrical engravings; Kuniyoshi focused on the military-historical genre in his older years. Their works stand in stark contrast to those of the 18th century, using more complicated composition, with vivid colours and a move away from traditional poses. Their figures’ ‘movement’ lent more realism. Kunisada and Kuniyoshi each published thousands of engravings and illustrated dozens of books, while training young artists at their studios. They were known to all.

In the 19th century, Utagawa school came to the fore, nurturing two outstanding masters: Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861). Both led in the genres of yakusha-e and musha-e. Kunisada began as an artist of bijin-ga, but later created sketches for theatrical engravings; Kuniyoshi focused on the military-historical genre in his older years. Their works stand in stark contrast to those of the 18th century, using more complicated composition, with vivid colours and a move away from traditional poses. Their figures’ ‘movement’ lent more realism. Kunisada and Kuniyoshi each published thousands of engravings and illustrated dozens of books, while training young artists at their studios. They were known to all.The Head of the Department of Foreign Arts at the National Art Museum, exhibition curator Yelena Senkevich, tells us that the Hermitage stores nearly 1,500 Japanese engravings; just over sixty ‘pearls’ are on show in Minsk. She notes that these works are unique not only artistically but in their number. “In spite of this art form having been mass-printed, with each Japanese master (especially in the 19th century) enjoying around 200 imprints for each work, few remain today,” she laments.

Most of the works on display in Minsk are devoted to 19th century engravings, created by Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Kuniyoshi; their creativity, in many respects, guided that of European art. Ms. Senkevich tells us, “Works by these masters were collected by many European artists, including Vincent van Gogh; this Japanese art made a huge impact upon him. Japanese engraving influenced European modernist style.”

Most of the works on display in Minsk are devoted to 19th century engravings, created by Utagawa Kunisada and Utagawa Kuniyoshi; their creativity, in many respects, guided that of European art. Ms. Senkevich tells us, “Works by these masters were collected by many European artists, including Vincent van Gogh; this Japanese art made a huge impact upon him. Japanese engraving influenced European modernist style.”Hermitage Director Mikhail Petrovsky, who visited Minsk, noted that he is pleased with the display at the National Art Museum. He emphasised, “I toured the exhibition with pleasure. It’s not easy to exhibit graphic works and these engravings are rarely shown in such numbers. Even for me, it was interesting to see. This particular Japanese art influenced European art and its modernist roots. In itself, it is interesting and very beautiful. For the Belarusian exhibition, we chose the theme of Tokyo’s elegance: its theatres, entertainments, and long admired nature. Of course, Tokyo is now a blaze of activity and lights. Japanese culture reveres the combination of refinement with the present: softness in contrast to strength.”

Certainly, the exhibition at the National Art Museum is a landmark event, featuring works by globally prominent masters. They allow us to enter a new and surprising world: that of traditional Japan society in the Edo epoch.