During the time of Tsar Peter the Great, Russia saw increased interest in Western European science and technologies, including the manufacture of clocks and watches. In 1757, the Academy of Arts opened in St. Petersburg, with inventor Ivan Kulibin heading its mechanical workshops from 1769 until 1801. These became the major hub of instrument engineering, attracting various scientists and inventors from the West, who considered co-operation with the Russian Academy to be an honour. They donated their research and participated in competitions organised by the Academy.

Demand for clocks and watches rose rapidly in the 18th century, inspiring the government to launch two state plants manufacturing of clocks and watches in 1769: in Moscow and in St. Petersburg. The Moscow workshop existed only until 1778 but, in 1770, its workers installed a chiming clock inside the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower. A third such factory opened in 1784, at the initiative of Prince Grigory Potemkin-Tavricheski, the owner of Kupavna silk plant.

Located on his Dubrovno estate, in the Mogilev Province, the workshop produced refined technical innovations, with Peter Nordsteén at the helm.

Born in Sweden, he had been living in Germany and arrived in Russia at the beginning of the reign of Empress Catherine II, holding a patent from the Stockholm Academy of Sciences for a new design of pocket watch.

The Empress wanted to develop industry in Russia and so set about attracting foreign masters. At that time, clocks and watches were luxury goods only affordable by the wealthy. In order to win over Empress Catherine II, Mr. Nordsteén presented her with a unique ring containing a watch. This so impressed her that she immediately appointed him as head of the Academy of Arts’ watchmaking department: the first to train watchmakers. Fortunately, being a favourite of Catherine, Grigory Potemkin was permitted to ‘poach’ Peter Nordsteén for the factory on his own estate. Thereafter, Nordsteén’s name was inseparably connected with 18th century watch production.

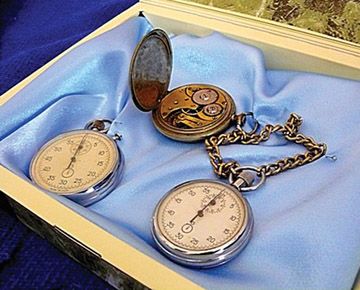

Worthy exhibits for museum

The move to the Mogilev Region seems an unlikely attraction for the inventor, but he had built up debts in St. Petersburg, despite being given a state apartment with heating and light and a good salary of 250 Roubles a year. With creditors in pursuit, he accepted Potemkin’s offer, which included a salary of 12,000 Roubles over 10 years.

His obligations included apprenticing 30-40 reasonably literate children from garrison schools, and he was prohibited from importing machinery or other tools without paying duty. Mr. Nordsteén even had to support his pupils at own expense. Nevertheless, his workshop proved viable and operated until war broke out in 1812.

Over a relatively short time, he trained 33 teenagers in various types of clock and watch production. He wrote that they learnt ‘how to make a variety of pocket watches, wall clocks and large, fighting timepieces, alongside cases, and how to draw figures on the faces and enamel them, as well as making chains for watches, engraving and gilding, constructing springs, and making various saws and geometrical tools’.

The workshop operated under the principle of division of labour, with each master fulfilling a certain operation, before assemblage and regulation. They produced up to 10 pocket watches a month, supplying the imperial court. However, after Potemkin’s death, the treasury purchased the factory. At the order of the Empress, in 1795, several dozen young boys and girls were transported first to Moscow, and then to the nearby village of Kupavna, to continue the work of the factory. It finally closed in December 1804, unable to compete with European manufacturing.

Dubrovno lost its chance of supplying components to Kupavna but archives tell us that, on May 30th, 1793, three years before her death, Empress Catherine II issued a decree commanding that ‘peasant families specialising in the making of cloth, clocks, galloon lace and candles, who had originally come from Dubrovno, should be resettled in Yekaterinoslav’.

At that time, the city (now Dnepropetrovsk) was growing in size, and had 285 families (1792 residents). It became known as Dubrovensk, and then Sloboda Surskaya (from the name of the River Sura, which flows into the Dnieper).

Among the settlers were first class watchmaker graduates from Dubrovno Plant, including Fiodor Kowalsk, who joined colleagues in opening a studio in Yekaterinoslav. By the early 19th century, it had become a Russian centre of manufacturing for such devices, using techniques first developed in Dubrovno.

By Alexandra Udaltsova