Grodno artist Vika Ilyina has an old, mechanical alarm clock which she likes to take out when feeling melancholy, to stretch its spring. She places it on the table and listens to its rattling and clicking, recalling the past with nostalgia.

Vika’s studio is inside an old water tower, while she lives in a pre-revolutionary house in the centre of Grodno. Both have wooden stairs, which creak and sigh, and the banister is painted in ordinary red primmer. The studio, house and city look so mysterious and ancient, slightly forgotten but interestingly revived in the memory.

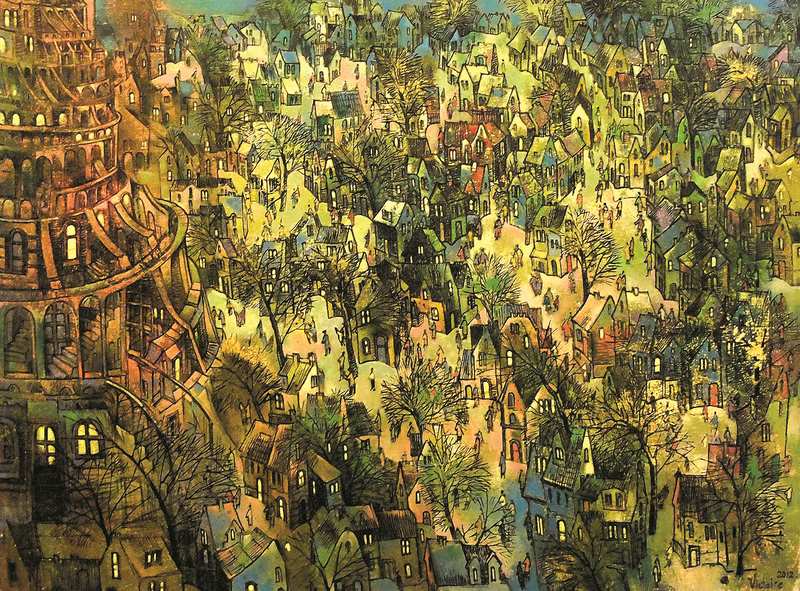

Her pictures resemble dreams, both colourful and black-and-white, featuring strangely drawn cottages, trees and towers. They resemble old espaliers, where colours fade and are graduated: from top to the bottom. The colours give the impression of depicting recollections — being unexpectedly bright, blurred or dim. Victoria speaks hastily, as if afraid of missing something vital.

She tells us, “After graduating from university, I had no plans to lecture. My mother was my model, having taught for many years. I saw that being a teacher can be stressful and takes a great deal of energy. While studying at the Institute, my teacher, Oleg Khodyko, said that a great number of pictures had been painted and that a few dozen or hundred more wouldn’t change anything. Meanwhile, teaching children (or adults) to draw and appreciate art is a civic duty, as well as a kind deed.

In 1988, I moved to Grodno, in search of a studio. However, I found a job instead, at the local art school. I remember it so well, as those times were hard: we had to paint the floors and walls ourselves, and make repairs, carrying heavy furniture. I decided that the time had come for me to leave the school, having paid my artistic ‘debt’.

You still spend a great deal of time teaching, so when do you find time to create your art?

The school doesn’t just ‘take’, it also ‘gives’, teaching discipline and how to communicate with young people, which is very important. Children can tell you so much; it’s interesting to see them growing into adults. Painting doesn’t take much time; it’s a pleasure rather than a labour. I simply come to my studio and paint a picture.

Do you show your works to the children?

I do sometimes, when they deserve it! I take them into my studio and to those of neighbouring artists — to see and learn.

How did you become an artist?

It happened unexpectedly. I could choose either medicine (as do those with good grades often) or art. I think, sometimes, now that I might have brought more benefit to people if I’d gone into medicine. Sometimes, there’s no place on my shelves, as all are covered in pictures. It makes me rather embarrassed. However, they all sell when I have a show, and I then have ‘room’ to paint something new.

My own teacher of painting and technical drawing at school influenced my decision. She was a true personality: tall, stout and authoritative. Everyone fell silent on seeing her. Those selling art supplies at nearby shops always knew what pupils from school #12 needed, as she convinced everyone that drawing and painting are more important than mathematics. In her classes, she would tell us stories of artists and, even now, I remember how Repin entered the Academy, painting wolves and a single man on the steppe. Many of her pupils later became artists and she convinced me to find fulfilment through art: I believed her.

Do you use open-air sessions?

No. I paint in my workshop. Sometimes, I draw shrubs in summer, but I tend to invent rather than draw from real life. I tend to develop the plot while working. I start with a canvas, and paints and surfaces come later. I sometimes spend a lot of time on a single work, giving it great consideration, and starting anew many times.

What are your pictures about?

I often hear this question, even from collectors. I don’t know what my themes are; I try to invent content but usually fail. What themes can water, trees or snow have? I’m sometimes reproached for drawing similar plots for years and am told that I need to invent something new. However, even Modigliani (if you think about it) painted similar pictures over and over, as if drawing the same picture repeatedly. Yet, he is so well loved and well known. Not everyone can be as inventive as Picasso, distinguishing new artistic trends.

You’ve been travelling abroad. Are these commercial trips?

I’ve not been abroad for a long time. I married and my elder son was born, followed by the other 12 years later. I also had a dog and everyone needed my help and care. Now, the children have grown up and I tend to travel outside of Belarus to visit open-air workshops. I don’t do so with sales in mind but to absorb the atmosphere and invigorate my mood. I’m sometimes lucky enough to attend a major show. I’ve seen Chagall’s works, gathered from various museums. It was a great exhibition.

What inspires you? Do you visit the countryside?

I don’t now but I used to, going to my granny’s house in a village. Sadly, it burnt down, but it remains a special place for me, as I spent my childhood there and my dearest memories are connected to this place and time.

Looking at Victoria’s works, it seems to me that I can hear an old alarm clock, from her granny’s village house. There is the impression that I can hear time passing, set aside from our daily routine. I want to stop time, to recollect warm sand, cold snow, clean water, trembling leaves and all which we can’t describe with words.

By Vladimir Stepan