The picturesque canvases and watercolours of Zoya Litvinova are stored in the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus. It is due recognition of her as an artist — after all, works are do not accepted into the museum without reason. Litvinova’s pictures are also stored at the Museum of Modern Fine Art in Minsk and at the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, in museums of Riga, Novosibirsk and Bishkek, and also in private collections and municipal collections of Austria, Germany, Italy, Denmark, Holland, Republic of South Africa, Israel, the USA and Canada.

In 2005, Litvinova was awarded the order of the Ministry of Culture of France for merits in the field of art. The author herself considers art as international, and is happy that her work is spread all over the world. At the same time, she highly estimates the national school of painting, though she believes that this school is still in the formation stage, but already has a certain importance.

The Honoured Figure of Arts of Belarus, Zoya Litvinova likes the prepared spectator because philosophy is put into the work of an artist. Here is one of her statements: “I am a traditional artist. I am a contemplator, who ‘feeds’ on reality, and consequently, I do not see sense in breaking ties with it. I do not see an occasion to refuse figuration, though abstract is also very interesting to me. And in general, painting for me is a unique means for the embodiment of spiritual reality existing around us, but not visible to the eye.”

And how do you treat such a forgotten and even neglected aesthetic category in art, as ‘beauty’?

Well really, this concept has ceased to be used in our life. Well, who if not an artist should think of Beauty, to create Beauty. Beauty is harmony. And what is life without harmony?

In 1986, in Minsk, the group of artists created the creative association Nemiga-17. Adherents set before themselves the task, as critics then noticed, to update poetics and the plastic language of domestic painting. On the wave of the first reorganisation years, artists of all republics of the former Soviet Union, more than ever, sharply felt the urgency of the problem of national-cultural identity. The period of formation of Nemiga as a uniform (at all variety of individualities entering into it) creative collective, the formation of its concept fell just on these years. Even in the name of the group, the artists aspired to underline ties with deep layers of national history and culture.

Nemiga is not only a street with a workshop where the idea of the association arose, it is also the name of a river which no longer exists, the bank of which in 1067 became the field of an historical battle between the armed forces of Polotsk and Kievan dukes. The Battle of Nemiga is described by the author of the Tale of Igor’s Campaign and the first mention in ancient annals of Minsk is connected with this particular event.

Nevertheless, in the development of national problematics, Nemiga artists never rejected the historical or ethnographic theme and plot. The decision of this task they transferred into the sphere of exclusively plastic searches. They expressed the recognition of their own national identity in aspiration to find an artistic language which, with all its modernity, would be genetically connected with the traditions of culture of Belarusians. Already, at that early stage, a creatively oriented attitude to national tradition, to world culture as a whole was peculiar to members of Nemiga.

Nemiga brought into Belarusian painting an interest and taste to expressional, plastically rich pictorial form, to associative metaphoric speech. Colour has always been and is the basic form-building component for painters of this creative commonwealth. After all, it is the space of colour-plastic experiments where the search for possibilities of special expression and vivification of form happens. Differently, colour for them is the main graphic and expressive means in achievement of ideologically-emotional depth and the substantiveness of artistic image.

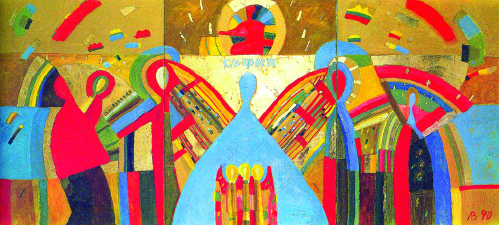

Unlike their younger colleagues, Litvinova was included into the composition of the association as a mature master. But at this particular time (and most likely it is not casual) radical changes happened in her creativity. Her artistic vision became emotional; her concept of colouring became complete, while her plastically-constructive solutions of canvases gained verified logic and impressive monumentalism. Litvinova does not refuse figuration, but she deprives the form of reality, consistently and organically connects figurative forms with abstract and places them into conditional space. Her main task is the consecutive penetration into the deep essence of things and phenomena. She is not a concrete artist, impressionistically short moment of life, but a philosopher who comprehends the world. Therefore, her reference to bible themes or to themes of love and human loneliness is organic and not so banal in her creativity. For the same reason, this or that creative means which at times are absolutely cloying, get a novel and surprising power of transformation of the images in her canvases.

Unlike their younger colleagues, Litvinova was included into the composition of the association as a mature master. But at this particular time (and most likely it is not casual) radical changes happened in her creativity. Her artistic vision became emotional; her concept of colouring became complete, while her plastically-constructive solutions of canvases gained verified logic and impressive monumentalism. Litvinova does not refuse figuration, but she deprives the form of reality, consistently and organically connects figurative forms with abstract and places them into conditional space. Her main task is the consecutive penetration into the deep essence of things and phenomena. She is not a concrete artist, impressionistically short moment of life, but a philosopher who comprehends the world. Therefore, her reference to bible themes or to themes of love and human loneliness is organic and not so banal in her creativity. For the same reason, this or that creative means which at times are absolutely cloying, get a novel and surprising power of transformation of the images in her canvases.

What forces feed the creativity of Litvinova? She considers that when a person dares to become an artist, he or she should remember that art will be the master, the only master, and that it is necessary to renounce much in life. And maybe the force of creativity lies in the background?

She was born in a village in the Vetka District of the Gomel Region. Her childhood fell during the difficult war and post-war time. It was terrible in the days of the war. During the post-war years there was nothing to eat and people lived very poorly. And all the same, childhood is childhood: life and pleasure won, feelings were strong and bright. Also, there was something very important in her life, as if in understanding of a secret.

“I grew among the fields, woods and water,” Zoya Litvinova tells. “I perceive the nature of Belarus through these symbols. All was alive and mobile. At times in the shine of water or the trembling of foliage I saw sliding, arising and disappearing airy transparent beings. I absorbed everything — both nature, and people, and those tales, which surrounded us. I very much liked simple old women, they gathered in the evenings at our place and told fairy tales about different miracles, sang and told fortunes. They came after work, when twilight came. Since then, twilight has been a special time for me. Here is an almost imperceptible facet meaning a transition from one condition into another, from one form of existence into another. It is an exciting and painful, mysterious and intriguing moment. It is as though I have passed a through a special threshold. It was interesting to me, what was behind it. And it was terrible. I wanted it to proceed, but I sometimes escaped and hid.”

After all, in the content of these fairy tales and stories, in their secrets is my imagination which has become a special means of children’s clairvoyance, I began to see through the forms and I began to paint.

While today, already being a person with big life experience, Zoya Litvinova estimates her creative youth rather favourably “I have always known what I need and want. I have never come to terms with my conscience. Therefore my life, I will tell openly, was rather difficult. I graduated at the monumental department of the Minsk Theatre and Art Institute and orders somehow supported my life. I solved problems directly in the workshop — alone with my painting. But I have never done what I did not like, what was not interesting to me — especially now. It is necessary to get used to my painting, it is not so simple to perceive it. In due course, it gained greater light and brighter colours.

It is connected with the development of the soul, I think. I am a person who is interested in myths, legends

and religious themes. It is not casually that throughout the last 20 years, bible themes have been the basis of my creativity. Paintings change, it is natural. I have always tried to open something in myself, something to overcome and not to follow already found plastic solutions. I very much like fresco.”

and religious themes. It is not casually that throughout the last 20 years, bible themes have been the basis of my creativity. Paintings change, it is natural. I have always tried to open something in myself, something to overcome and not to follow already found plastic solutions. I very much like fresco.”

Your creative manner is often called fresco.

Yes, I am fond of spiritual painting. It seems to me that nothing higher than fresco was created in the world. I consider that it is a realistic manner. After all, we depict reality not only in the way we see, but also a reality in which we feel a spiritual reality. It is everywhere, but we feel it inside. And how we express it is another matter. So my painting is realistic, while I am a realist.

Probably, there would also be those who would argue with this statement, who would disagree with it.

I never turn away from nature. Another thing is how I process it. What it gives me and what I can express through nature.

Do you convey in your works the reality how you see it?

Yes — and also how I feel it. After all, physical sight is identical at all people. For me it is important what means I will use to express it.

Even if their form is far from realistic?

Certainly. Reality will be more interesting at the expense of life. And when we copy off, we receive an imitation. It is not correct.

But let’s take the portraits which you created. They are more realistic.

Naturally. In a portrait, I express the character of the person. Certainly, the portrait should look like a person. How I feel it? What I want to underline in it? How to express it? I want to a find plastic solution to all of these. I have always been interested in portraits. I have painted a lot of them.

And yet you are known more as a compositional painter.

I changed, but I am always recognised. I changed because I had new experiences, felt something new. We become different with life experiences. Now I don’t paint subject painting, but all the same, I am knowable, because it is my form, my colour, my plastic methods.

Do you attach great value to colour in your works?

For me colour is of great importance in the solution of the theme.

The colours which are most present in your pictures, are they in keeping with you?

I love light and cheerful colours. I consider that our life is so difficult, that we should help people to find pleasure in it. It seems to me that this task is required for the artist.

In the 80s, people were not ready to perceive you and other artists. Has the perception of your creativity changed?

Yes, certainly. We are not young people anymore. And if we established ourselves as artists, then we are successful. If not, then not. I was invited to Nemiga when I was already a famous artist. In those years, we were exhibited in groups. But then the time came when group exhibitions become less in vogue and personal exhibitions were more interesting.

What exactly affected choice of your creative manner.

It is the result of my daily work. Painting needs to be experienced, it needs to be felt. Everyone discovers something for oneself as we are all different. Everyone finds what he or she wants.

And is there an excessive aspiration to individualism in your manner? Does such circumstance — that your manner should be distinct from others — weigh upon you?

Everything is absolutely involuntary. It does not disturb me. Though nearly fifteen years ago I put before myself other tasks — it was interesting to me to solve important things. I have come to other plastic language — abstract, not subject. But it is recognised. It is my language with my special profound philosophical importance of symbols. Symbols are repeated all over the world, they are known. For this reason, art is probably international. Wherever you show a picture, people who are interested in it, are able to read the content.

Has abstract painting become basic for you?

No. It does not mean that I am not interested in humans. I still do portraits. In due course, abstraction emasculates and we can come down to simplification — I do not want that. I do not want to lose my ties with the real world. It is very important for me, because I am fed by the reality in which I live, which I feel. Actually, it is work of soul — that important part of creativity. After all, when we just copy off nature, we become slaves, and we should not allow that.

But after all, abstract painting as if transfers to another world?

Yes. It is very interesting.

But it is possible to go overboard…

For me, as I’ve already said, it is very important not to lose ties with reality.

Let’s talk about traditionalism. All the same art is based on places where the artist lives, on the atmosphere connected with reality.

All of us are products of our time and products of our place. Because we love it, we have absorbed it. I, in spite of the fact that I like to travel, cannot remain somewhere more than a month. I want to go home. I consider myself a character national artist. I hear about myself: ‘Character artist’. It means that there is something in my painting belonging to Belarusian art, despite my internationality. It seems to me, that our national school of painting is still in the formation stage. We can speak about the Russian school, about the French. All artists who studied in St. Petersburg or Moscow after the war, they left the Russian school. And we are its followers. I consider myself a representative of the Russian school on the basis of which the Belarusian school starts to develop.

After all there were artists — natives of Belarus — like Chagall, and Soutine.

We say with pleasure that such geniuses worked here. Certainly, there is an interference of all schools; especially at this time, when we are so connected with the world. Now, Belarusian artists are different, at times it is difficult to distinguish them from European artists. It seems to me, that we should not give great attention to that. If an artist becomes more considerable they also become also more national.

What is more in your works, figuration or figurativeness?

Figurativeness should be present in every work. If you set a task, you should solve it figuratively. And it is not necessary to divide the stages of an artist. All the tasks which you set and solve are different. Abstract painting also bears in itself a figurative beginning, but images are different, not real. During recent years, I began to paint flowers. Earlier, it seemed to me that it was boring, but now I have started to do that and it is very interesting to me — just like daily exercises for a pianist. But it is possible to do them even creatively.

I will repeat once again — I attach great importance to colour, the conditional language of painting, because it is the whole world, a special reality on a canvas. In the late 80s, gold appeared in my painting. I introduced it as an element of the sun, as the power of spirit. Near to the gold it is necessary to put such a colour which would sustain this strong, bright power accent. Painting becomes more conditional and richer with colour. For me it is very important.

Do abstract works have a more philosophical comprehension?

Yes, there is another philosophy. In one of my works, the world is spiritual — a world of the sky and the earth. There are signs of power which penetrate into these both worlds, but how does one depict them? How to find concrete real plasticity? How do we experience it? Preparation and general knowledge are very important here — philosophy, erudition and wide reading. All these demand work of the soul; not only mine, but also of the spectators.

Is it possible to say that you always interpret in your works?

Yes. I never copy. Even if I paint a landscape from nature, I move or remove something, it is impossible without that. It is a creative process.

At what level do you think Belarusian fine art has reached? On what stage is it now?

It’s on a good level. Today, Belarusian fine art is very much quoted. The national school is gaining in importance, but the school is created by individualities; each one bringing originality into this school. When the artist is healthy, the artist works and hopes that they will paint something very important. I think that if the work of the soul has not stopped and if you are alive inside, then you are capable of creating.

By Vktor Mikhailov