Minsk is well endowed with respected ancient forests, although the newly planted areas created countrywide are similarly favoured by admirers of green spaces. Many have fond memories of the age old Dubrava (oak-grove) which adjoins the districts of Kurasovshchina and Brilevichi. The grove, located close to the southwest suburb of Minsk, extends over 24 hectares. Residents of the nearby village of Shchomyslitsa tell stories of ancestors walking in this forest, where ancient Oaks with girths of more than a metre mix with Pine, Fir and Larch. It was the large number of Common Oak trees in the forest that led to its name of Dubrava.

At the beginning of the 20th century, these local lands belonged to the family of Count Hutten-Czapski: the first to bring Oaks into the region. Other rare species were planted in the 1930s, including the Northern Oak, Manchurian Walnut, Black Oak and Douglas Fir. Scientists began to study the behaviour of trees, researching how well they survived and adapted to the climate and local flora and fauna. Now, nearly 80 different rare species of trees grow in our forests, as well as more than 480 species of plants, some of which are included in the Red Book of endangered plant species. In 1986, the oak-grove was declared a natural park of national importance and was transferred to the care of the Belarusian State University in order to ensure its security and future as a conservation site.

The state places a high priority on the maintenance and upkeep of urban green areas and actively promotes new schemes. The Government is keen to show active involvement in the restoration and protection of the landscape. Traditional cleaning of forest areas in the cities is carried out every year, ensuring that trees are not suffering from pollution, are protected from drought and are otherwise in no danger of extinction. This autumn, at the beginning of September, the Minsk City Executive Committee and the Minsk forest-park enterprise organised a subbotnik (voluntary unpaid work). Across the capital, more than four hectares of city forest were cleared of debris. My family and I were happy to join in, collecting rubbish in our favourite forest glade in Slepyanka, close to which we live.

This year autumn was sunny and warm and my family often enjoyed walks in the forest. We admired the small tortoiseshell butterflies, silvery spider webs and the warmth of the first ‘Indian summer’ for a long time, we inhaled the aroma of pine needles and falling foliage, chasing leaves and sitting round the fire which we kindled in a brazier.

In my schoolgirl days, I was dismayed to learn on a family picnic that no more fires were allowed on the ground. I was disappointed that the charm of those black forest fire circles would no longer be seen; I thought it would be an end to the magic of feeding branches into the fire and staring at the colourful and bewitching tongues of flame. My disappointment was short lived, as my father soon bought a small brazier for our family walks. Large public braziers were later installed and charming traditional arbours added. As an adult, I understood the decision to ban ground fires and began to appreciate the safety reasons. In many respects, these measures have allowed humans and the forest to exist in harmony, to the benefit of all.

I feel an immense pride and privilege to live in Slepyanka, where there is such a great variety of Pines and Firs, Limes and Birches, Mountain Ash and Alder trees. Apart from the pleasure of the forest itself, there are health benefits for my children and me; the health giving properties of plants and trees are well known. Recent research shows a link between the phytoncides emitted by trees, and increased activity of anti-cancer antibodies in humans. Looking to the future, our investment and care now will lead to increased health and pleasure benefits for future generations, perhaps from the very Lime trees being planted today.

Each autumn morning, I observe mist floating over the water in the grey pre-dawn silence. It seems to me that the fog knows all, but says nothing. Where the forest weaves along the canal path, the mist, trees and birds converse, interpreting nature into feeling. I imagine that even inorganic objects are capable of breathing and emotion. We naturally personify inanimate objects when we say: the sun awoke, clouds are looming, and the forest stands gloomy or threatening. This figurative way of thinking enriches our speech and imagination. For me it is only nature that inspires me to think like this. My imagination is poorly motivated by lines of dirty cars standing in traffic jams on Minsk Independence Avenue, skyscrapers, the concrete jungle and grey landscapes. How fortunate are those of us who have an alternative view! From my city apartment, I can admire the dawn mist settling on the water of the canal and, in less than five minutes, I can breathe the forest air outside.

The trees care little for the day or time of year; the forest breathes peacefully: an ancient inhabitant of the city. If you open the balcony door, you can feel its fresh breath at once. It is the neighbour who is always at home and loved by young and old alike. Despite not always being cared for in the best way, it responds with silent grace, giving the natural world to us regardless of lack of attention. Plunging into the forest world, I feel an immediate sense of relaxation, as if my cares and troubles have been lifted from my shoulders and I am free, for a while at least, to dream. I might choose another occasion to write, working amongst the peaceful atmosphere in isolation or with the family, with a flask of tea, waiting impatiently whilst my husband cooks aromatic kebabs over the brazier. It seems to me then, that the forest is in harmony with us, whatever we choose to do there.

My forest of Slepyanka — friend, health giver, and ecological filter — is but a small part of the green area of our country. In the last five years, this area has tripled. Over the last sixty years, Belarus has doubled its volume of forest, reaching approximately 9.5 million hectares. The forest is changing right before our eyes, with companies such as Belorusneft developing conservation initiatives such as the impressively named ‘Choose Green Refuelling!’ Each participant has the opportunity not only to lay down the foundation of the future forest by nominating a tree to be planted, but to track the progress of their own personal tree online. With so many people supporting the scheme, a 1.5 hectare area of waste ground close to the city has now been planted, creating a small forested area for the future. This is not an isolated event, happily for those who care about conservation; in cities across the country, volunteers are planting large areas of trees and, as a result, the map of Belarus is being slowly replenished with new green districts.

A short trip back in time with the elks and forest snails

In our fast-paced urban lives, city children have become used to playing hide-and-seek behind the wheels of parked cars and drawing on concrete. I am a native of Minsk, a ‘child of asphalt’. I silently rejoice that I can retreat to the Slepyanka forest to escape from the July heat or November wind. The presence of a network of small paths between the trees alerts me to the fact that I am not alone. This web of tracks is evidence that I am not the only forest lover to wander through the leafy serenity. Slepyanka is known locally as a village-city district due to the abundance of trees. The forest stretches up to the wide motorway surrounding our city.

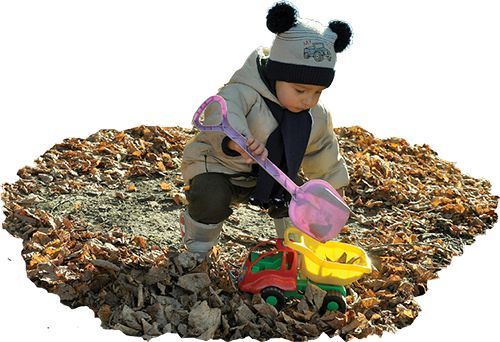

The first mention in history of this wooded place is found in documents from as early as the sixteenth century. Later, it became the location of a military firing ground. Eyewitnesses tell stories of their fathers, when they were boys, playing with the helmets they found in the forest and storing rusty cartridge cases in them. It seems that the forest keeps many secrets. It is difficult to imagine that on the ground where children now gather pinecones with such delight (‘pinecone hedgehogs’ as my daughter calls them) our ancestors walked without knowledge of technology.

It is not only children who love the forest; once, walking there with my little son after the rain, I was witness to an invasion of snails. At first I thought to use them to help me teach my child to count but, when the figure exceeded 20, I decided to play pretend games with the help of these horned creatures. Our snails participated in stories and races throughout the afternoon. How wonderful, I thought, to teach my child using the book of nature rather than a DVD or television programme. However, the world wide web has advantages: it allows me to watch videos and read about one of my favourite pictures, Morning in a Pine Forest by Ivan Shishkin, which I often recollect when walking in the forest.

It is not only snails that inhabit the forest. There have been several reported incidents of elk leaving the cover of trees and jumping onto the road in front of cars. Motorists need to be aware of the danger; a collision with an elk can be serious and has caused the traffic department some difficulties in the past. Fortunately, no one I have spoken to has ever met an elk on a narrow footpath, so my walks can continue in peace!

Children’s Railway in Minsk

City plans for forest

Unspoilt forests have their own charm though, even here, where planning has not yet reached, there is evidence of local ‘cultivation’: trampled paths, stumps with ‘hats’ of old forgotten newspapers, benches quickly cut, hooks for hammocks carved from boughs sticking out of tree trunks and a children’s railway, complete with miniature trains. The railway appears suddenly, hidden from view behind the dense green foliage until the last moment. Like a measuring tape, it snakes away into the distant trees, under the road bridge, effortlessly mixing nature with civilisation. Despite its listing on the children’s Belarusian Railway site, everything about it is real. There are reduced size diesel locomotives with carriages, traffic regulations and locomotive drivers, conductors, stationmasters — and passengers, of course. The children’s railway, opened on July 9, 1955, differs from the main line only in the width of the gauge (750 mm — almost half of the standard gauge) and in its length (only 4.5km, instead of thousands, while the length of the main line is 3.79km). As for the rest, it is exactly the same as the Belarusian Railway. This narrow gauge railway is a good example of co-operation between a real railway enterprise and educational institutions for both adults and children. Youngsters feel enormous pleasure while standing on the miniature station ‘Sosnovy Bor’, peering with concentration and amazement at the railway line forking in two between shaking birch trunks; listening attentively to the whistle of the slowly approaching carriages.

The charm of the wild unspoilt forest is certainly under threat, but from plans and projects designed to make it accessible, sustain and conserve it. Minsk forest-park enterprise has plans to transform the remaining untouched areas of city forest across various city districts into forest-parks: places for comfortable civilised recreation, with fountains and footpaths, in the manner of the botanic gardens of the past. So far, 96 hectares of landscape have been reforested or aesthetically changed, the third largest project of its kind in Europe. It would be wonderful to include small ‘botanic garden’ areas within these parks. City plans include designs for forest-parks with a sports bias: skate parks, cycle tracks and platforms for power lifting are all being considered in the long-term plan. Until these materialise, we are free to enjoy the forest as it remains, a place where blue tits jump from branch to branch, squirrels scurry up the trees and only the insistent hammering of a woodpecker breaks the silence.

There is a lot to do in the forest

Having watched the next train depart with waving hands, we go into the trees to collect pinecone ‘hedgehogs’, count acorns and dig chestnuts in the fallen, dry leaves (perhaps they will sprout in the spring). We will play games with mountain ash berries, seeing who can throw furthest and make a fishing rod from a birch branch, attaching a yellow oak leaf to lure goldfish. To our great pleasure, in autumn, there are always Maple, Poplar and Birch ‘goldfish’ leaves in the water. Then, tired and happy, we return home, perhaps returning back tomorrow or on another day.

By Alisa Krasovska