Мost artists’ studios resemble on another, differing only in their location: Paris, London, New York, Chicago, Grodno, Vitebsk, Moscow or St. Petersburg. Some studios look onto snow-covered fields or village life, or dark forests. Roman Zaslonov’s Minsk workshop faces an avenue and the grey winter Belarusian sky. Roman has split his time living in France and Minsk for two decades.

We met at his Minsk studio to chat. He welcomes me with humour, pondering the hand of Fate in his work being featured at the National Art Museum: a place he visited initially only as a visitor, to see the works of classical painters. “Who would have thought that, one day, it would feature a huge banner inviting people to my personal show?”

Roman, how did you end up in France?

In the late 1990s, I worked with a French gallery, organising several shows. I often brought pictures and, some time later, the gallery owner asked if I’d like to live and work there. While some artists move irrevocably, emigrating forever, with the accompanying rejection of original citizenship, broken ties and, often, homesickness (as happened to many artists following the events of 1917) my case is different. I travel between the two places often, and view Minsk as a permanent resident, although I’ve only spent about two years there of the past twenty.

Do you have feel like you have two homes?

No! On coming here, something switches on in my head, then switches off on my departure. I don’t feel that I’m going away. It’s different: in Minsk, I need to walk along the street to reach my studio and, in France, I simply need to open another door.

Removal of the studio. Winter. Oil on canvas. 2012

Do you have a different circle of friends here?

On coming to a new country at the age of 35, you don’t make the same friends as those you’ve known since childhood. However, a great many good people have come into my life. Over the first five years in France, we lived near Nice; now, we live in a village near Paris. People are different there, and didn’t warm to us initially. However, over time, we’ve established more friendly relations: people see that we are ordinary and have no intention of offending anyone.

Picasso came to France from Spain and Chagall also moved to France. Most French artists don’t have French names these days. I’m not taking away local employment opportunities and I pay taxes obediently.

Are you the only artist in your village?

No. Michel Levy — a famous sculptor in the region — lives not far from me. On National Legacy Day, I exhibited alongside Michel at the Mayor’s Office. There was a poster up, and local residents are pleased that such good artists live in their village.

I’m more eager to live in the city as I age, although Paris is complicated and expensive. Minsk is more convenient and friendly; it has warmth, which is lacking for me in Paris.

Has your lifestyle changed?

Only regarding my studio, since I don’t need to go out, putting on coat or shoes, to arrive there.

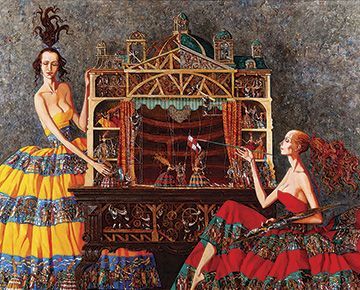

Final rehearsal. Oil on canvas. 2014

Tell us about your gallery, your themes and canvas sizes… Do you have deadlines to meet?

I haven’t had a deadline in years, rather painting what I wish, without restriction on quantity or size.

Do you have regular customers?

A picture has three stages of life. The first is in an artist’s head and in his/her studio. The second begins when the picture goes on show — either at a Paris gallery or Belarusian museum. This is often the last for many pictures, since they return to the artist’s studio after being exhibited. If a picture is sold, then its third stage of life is launched, as it may be resold many times, which I find pleasing.

I like meeting buyers via the gallery and I know many of them. Two even came to my Minsk show from Luxembourg, and had a wonderful impression of our city. They visited the Opera Theatre and tried our national cuisine. They view Luxembourg as a large village and Minsk as a major cultural centre (smiling).

Roman, are you in contact with our countrymen who’ve settled in Europe?

Of course. I see Boris Zaborov, Andrey Zadorin, Natalia Zaloznaya and Igor Tishin — although they work with other galleries. Actually, our past and our common alma mater help us keep in touch. We share a common past, having read the same books and having eaten the same food.

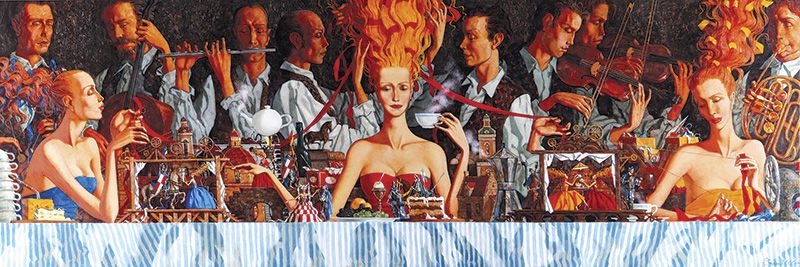

The red ribbon. Oil on canvas. 2014

How did you become an artist?

It’s an ordinary story. Sergey Katkov was my first teacher, and gave me my first new box of watercolours, as well as paper and a brush. It was a miracle! One of my first pictures was taken to a show and was filmed but they switched off the camera on hearing my answer to what I’d like to become, as I said a shepherd!

Then I became a pupil of Mr. Tkachenko, who made me feel that I could do nothing and that drawing was a very difficult process. However, on attending Vasily Sumarev’s studio, I experienced different emotions: it was endless fun.

My studies at the Institute were my next stage of development, and probably the most important. With time, I’ve realised that we learn most not from teachers (however wonderful they are) but from friends. That time was truly golden!

My time at the Theatre and Art Institute was also significant. It was known for its wonderful amateur concert parties, which were organised at the drop of a hat, in about a week, although they inspired months of recollections — until the next holiday.

Many of those hooligans — Volodya Tsesler, Sergey Voichenko, Dima Sursky and others — are now famous artists. In those years, they created a new environment, giving birth to a new form of art. Sadly, all departments are now separated, being situated in different districts of the city. That wonderful environment split.

Do you feel nostalgia?

When you leave the country where you once lived, you tend to feel nostalgia for your youth. On returning, of course, you cannot conjure past times. Truly, it’s impossible to swim the same river twice.

How did you find your theme?

It wasn’t easy. After my military service, I had no idea of what to do. I joined Mikhail Savistky’s studio but couldn’t draw landscapes there. After thinking for a while, I decided to paint artistes I knew; that canvas is now part of my show, since everything began with it. I began to invent. Probably, time will pass and my works will change again.

After chatting and recalling student days, we began to peruse his old works. Roman showed me large and small canvases, putting them on an easel, smiling. Those landscapes began his long path. Now, how much has been achieved. The road, grass, fields, stones and rivers, all have their own charm and significance.

P.S. The museum walls are decorated with his works, featuring red-haired beauties, Mediterranean towns, knights, flags, bright dresses, delicate glassware and thousands of other mysterious and attractive details. However, even these pictures sometimes depict Belarusian snow, woods, trees and flowers…

By Vladimir Stepanenko