My father did not like to speak about the war; when moved to, he was sparse in detail, recalling only the succession of events. No matter how much we (children, and then grandchildren) begged to hear his tales and how he felt at the time, he remained largely silent, preferring to go to the porch to smoke. Even when I needed to write an essay about the war for school, he would not share too many details. As we pressed him, the smile would fade from his face. His pallor would become grey, as if his life force were draining from his body.

First from the porch of our Ukrainian wattle house and then from that of our new home in Kharkov Region’s Volchansk, we’d often hear sharp coughing. It was sorrowful to listen to and, my mother said, was from having played wind instruments, rather than having smoked cigarettes. He used to roll his own, showing me how to do so when I was just 4 years old. I’d cheerfully fold the sheet, `pressing` it with my fingers, then tearing in half, sticking together the edges with saliva. Later, we used grey-white tissue paper for his tobacco: ‘Sever’, ‘Belomorkanal’, ‘Astra’ or ‘Prima’.

Photo Ivan Zhdanovich

He had played wind instruments from the age of 18, which had placed strain on his lungs. At university in Kiev, I’d bring him relatively expensive Herzegovina Flor cigarettes, as well as pipes, cigarette cases, and mouthpieces. I tried to convince him that it was better for him to smoke light cigarettes but he was set in his ways.

The mouthpiece of his baritone and, later, his trombone, always smelt faintly of tobacco. The mouthpiece seemed to possess its own magic and I still recall how it tasted, just as my fingers `remember` its smooth copper surface. In childhood, I wondered if musicians purposefully blew smoke from cigarettes into their wind instruments and to where it disappeared. My father joked that it settled on the walls. I used to love playing his baritone, pressing the shiny buttons. Meanwhile, I’d imitate smoking with a comb wrapped in tissue paper, although it was ticklish on the lips. Whenever my father was learning a new piece, I’d try to copy him on the harmonica he’d brought back from the war. I’ve no idea where it is now, and there is nobody to ask.

I’d often ask him to play a melody from the war years, Officers Waltz or Amur Waves, but he’d become sullen. My mother would asked for Modest Blue Kerchief and would berate him a little, saying, “Misha, is it so difficult for you to do what the child asks?” He’d sometimes capitulate, and would choose to play Amur Waves: why, I did not ask. Perhaps, this melody reminded him of his four years with the Pacific fleet. It was there that he was taught to play wind instruments and was photographed as a young seaman in his peakless cap. We still have the photo. I wish I’d asked him about his friends, where he went on leave, and where his unit was located.

His draft card reads: ‘Mikhail Cherkashin is classified as fit for service in the ranks and is accepted as a cadet into the school of experts of the Pacific fleet’. He joined on October 1st, 1932: the year in which the fleet was developed, `with the aim of strengthening Soviet boundaries in the Far East’. He was transferred to the reserve on October 1st, 1936, and soon met my mother. She was just 16 when she first saw the gallant seaman, taking a break between rehearsals for Tamila, staged by Volchansk folk theatre. She was playing the lead. She recalls being most impressed not by his attractive appearance but by his rich seal fur coat, which he wore over his sailor`s jacket, bought from Vladivostok. Nobody in Volchansk had such clothes but it was perfect for winter in Valuyki.

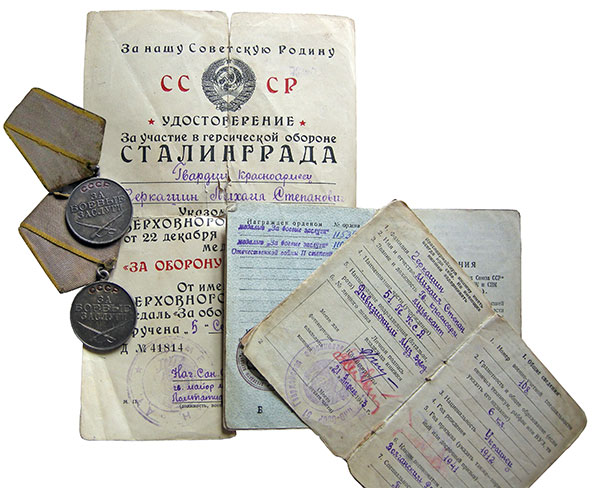

Awards and documents of Mikhail Cherkashin Photo Ivan Zhdanovich

Valuyki is also part of our family history. When the war began, my father was called up almost immediately, being directed 100km from Volchansk, into the 690th airfield service battalion, on the third day. Based near Valuyki, the district centre of Belgorod Region, he was appointed to manage supplies. In winter, he was passing through Volchansk by vehicle and managed to collect his young wife, then 20, and a 3-year-old son, my older brother, Yuri. My mother then found a job as an accountant with his battalion, leaving Yuri with the lady in whose home they were staying.

My mother recalled that it was ‘a terrible time of severe frost, with many pilots dying daily’. Quite a few wives followed their husbands to Valuyki, with their children, all believing that the war would end quickly.

In February 1942, my father was transferred into the 51st Guard Infantry Division’s Musical Platoon. While with the 690th battalion, he must have mentioned learning to play as a marine. His Red Army Book states that he was listed 108th in his military occupational specialty as a brass band musician. His medals are also listed, from his participation in the Battle of Kursk, near Stalingrad. His son Bogdan has them.

The anniversary of the Great Victory is inspiring me to reflect, pulling together as much information as I can about my ‘father`s war’. I was always proud of his musical talent, including his playing with the Volchansk Recreation Centre Orchestra, which entertained at holidays, concerts and funerals. His earnings were modest and I needed to go to kindergarten, so he took a second job as a household manager, where his pre-war sales accountancy training was useful.

For a long time I thought that my father was just naturally secretive. Only recently have I understood that I was mistaken, since most veterans (those I’ve seen on television and those I know personally) are reluctant to reveal everything about the war years: even those who are good storytellers. They have an instinct for self-preservation. It’s not hard to imagine how the horrors of war paralyse the memory. The faces of those who survived death and terror can become rigid at the bare mention of it. My father’s face became rigid too.

When pressed, he recalled washing bandages, and removing amputated limbs in basins, as well as burying those who had died, or dragging the wounded from a battlefield. There we other more mundane practicalities, such as being careful of what you said on the phone.

Sometimes, there was music too. One forum states: ‘Following the old Russian tradition, a musician platoon (part of many military divisions) would become the regimental orchestra, under a conductor, between fighting. Musicians performed patriotic military songs and marches, as well as folk music and popular melodies. Quite often, musicians would play during offensive fighting operations, to lift soldiers’ spirits and inspire them to attack. During combat operations, musical platoons would sometimes become hospital attendants, or trophy or funeral brigades, or they’d carry shells. They were still placed in the way of danger and were obliged to commit daring feats’.

It saddens me greatly that I can no longer ask my father about the Great Patriotic War. Did he have dreams about those years and his friends? Was he haunted by memories, or did he manage to put them behind him? How often did he write letters to his wife and son, who stayed with his mother Yekaterina, elder sister and his two small nephews for some time during the Nazi occupation. I can’t help but feel that I’d have more success in persuading him to chat these days. Back then, we rarely had visitors, and when they came, the conversation was on trivial matters. My knowledge of his war experiences stems from a few passing remarks, mum`s stories and remaining documents. I have only a sketchy outline of ‘his’ war: not enough to recreate the terrible reality in which he lived for 24 hours a day over three and a half years: over 1,300 days and nights.

My father died in January 1993, 48 years after being wounded in January 1945, when he was evacuated to the 414th hospital in Yekaterinburg (then Sverdlovsk). I remember him telling me that he’d been sent to Sverdlovsk, stressing the first syllable, as is characteristic of our Kharkov District accent. His war began on June 24th, 1941, and ended in April 1945, as his Red Army Book and draft card states. His documents note that he was treated at the 414th hospital, in Yekaterinburg, at 145 Mamin-Sibiryak Street. Now the House of Industry, it bears a memorial plaque from grey marble, commemorating the work of hospital #414, where my father was sent on being severely wounded by a direct hit.

January 16th 1945 was a day of shelling by enemy aircraft, and several young girl-signallers had died. Researching online, I’ve found that the 51st division was under Liepāja, headed to Königsberg. My father told me that his friends in the orchestra, Armenian Bagramyan and Jewish Mikhail Cherpakov, had pulled him out from under rubble. Both had recognised him by his felt boots, hemmed in large stitches with leather, in his particular style, as he’d been taught at the age of 12, as apprentice to a shoemaker. The craft saved his life.

Of all my father`s friends, he had particularly wanted to meet Bagramyan after the war. He’d been keen to go to Moscow for Victory Day celebrations and I’d thought about it too, during my student years. Veterans gather every year by the Kremlin, hoping to meet their brother-soldiers. It’s a pity that I never managed to attend with my father. While near Kursk, he was once taken to a Victory Day celebration, along with others from the Volchansk regional military registration and enlistment office. They went to the well-known memorial complex honouring Kursk Battle heroes, unveiled on August 3rd, 1973. My mother recalled that my father was very happy that day.

He managed to meet Mikhail twice: once, he came with his wife to Volchansk, staying with us; later, in 1981, my parents travelled to Riga to see the Cherpakov family. My father told me that his friend had written a book about the life of ‘war musicians` but I have no idea if it was ever published.

If only I knew more about how my father struggled during those war years. I feel I’d be richer, emotionally, for this. Online, I’ve read: ‘On the night of 26th January, 1943, the commander of the Don front, K.K. Rokossovsky, gave the order to penetrate Mamayev Kurgan and to finish the partition of the remaining, surrounded German troops. On the morning of that day, to music played by the soldiers’ orchestra of the 51st Division, they began the attack, alongside the 121st Tank Brigade and the 52nd Division. At Kurgan, they united with the 13th Guard and the 284th Infantry divisions of the 62nd Army, to fulfil their mission’.

Sergeant Ossetian Azamat Keytukov recorded: Keytukov fought with the 158th Guard Infantry Regiment of the 51st Guard Infantry Division. He had been at the Battle of Stalingrad and at Kursk, as well as taking part in Operation Bagration in Belarus. His most memorable fight was during the Battle of Stalingrad. One evening, the commander of the company came to Keytukov’s department to tell him that attack would begin at dawn. He added, “We’ll go with music, comrade sergeant!” At dawn, the company of submachine gunners took up initial positions for attack. Regimental musicians, led by conductor V.Y. Filatov, moved in. Rockets flashed in the sky and then ‘Internationale’ struck up. The artillery began to attack. Cheers of “Hurrah! Hurrah!” sounded over the entrenchments, and the guard division rushed forward’.

My father, a divisional musician, was there. With his companions from the orchestra, he assisted the wounded, as I know from my Internet research. Looking at ‘Feats of People in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945’ (<http://www.podvignaroda.mil.ru/?>), I found the surname Filatov and details of the conductor mentioned by Keytukov! Guard Senior Lieutenant V.Y. Filatov put forward Mikhail Cherkashin for the `Services in Battle` award list, on December 10th, 1943.

‘Feats’ writes: ‘Comrade Cherkashin, working in a medical and sanitary battalion as a hospital attendant-carrier, has a fair and honest attitude to work. During fighting from November 8th, 1943, to November 13th, 1943, he regularly delivered the wounded to the sorting platoon and to the operational platoon. Comrade Cherkashin, knowing neither weariness nor rest, renders aid to wounded soldiers and officers and helps evacuate them to the field hospital’.

On 27th December, my father’s award was issued, his second, after his medal ‘For Defence of Stalingrad’. His Red Army Book records: ‘For participation in the successful defeat of Stalingrad, and grouping of the enemy, Stalin gave two ‘official gratitudes’. Awarded a medal ‘For Defence of Stalingrad’ in 1943 [by order of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR, from December 22nd, 1942].

From history, we learn that the battle for Stalingrad began on July 17th, 1942, and continued until February 2nd, 1943. In that same year, my father was thanked officially for good combat operations in July, seeing off a German attack near Belgorod: known as the Battle under Prokhorovka and the Battle of Kursk (from July 5th until August 23rd, 1943). On July 22nd, 1944, my father was awarded his second medal ‘For Services in Battle’.

Seventy years later, it’s hard to say why he wasn’t commended ‘For Bravery’, as Commander Ivaschenko, the Guard Senior Lieutenant of the Medical and Sanitary Battalion, had petitioned for. His application reads: ‘During stationing, the Medical and Sanitary Battalion was located continuously in the forward group. He worked there day and night, without sleep or rest, rendering the fastest aid to those ill and wounded. During fighting from June 20th, 1944, onwards, Comrade Cherkashin delivered 450 wounded people to the sorting platoon. During his work for the Medical and Sanitary Battalion, he helped evacuate wounded soldiers and officers. He commands respect among the wounded and deserves the ‘For Bravery’ Governmental medal’.

My father also helped liberate cities across Belarus, during Operation Bagration: Polotsk and Vitebsk. He sustained two wounds: on January 20th, 1943, he had a contusion and, on January 16th, 1945, he was seriously injured.

In the awards list of January 23rd, 1945, signed by Colonel Kovalenko, Commander of the 49th Separate Polotsk Order of Alexander Nevsky and the Signal Regiment Order of the Red Star, I read official lines which truly touched me. I had to hold back my tears, realising that I hadn’t told my father often enough how much I love him and, never, that I am proud of him. The list reads: ‘Comrade Cherkashin, working as a lineman [written as lorry telephone operator], for a short period of service, proved capable of carrying out any set task. On October 10th, 1945, he carried out his obligations as lineman. Without stint, and under enemy artillery fire, he fixed over eight damaged communication lines in just 25 minutes, providing command with continuous fighting communication. His practical actions always helped the company command successfully carry out its fighting tasks. While on duty, on January 16th, 1945, during enemy bombardment, comrade Cherkashin was wounded. I petition the Military Council of the 6th Guard Army to award Comrade Cherkashin the ‘2nd Degree Patriotic War Order’.

Sadly, I have no idea under what circumstances he received the above; perhaps, it happened in hospital. Thankfully, my father’s Red Army Book remains. I wonder why he never showed it to me. His smell lingers between its pages: that scent familiar since my childhood. It may be my imagination. In 1987, he received an ‘invalid certificate’ for his time in the Second World War. He was proud of the privileges he received, though he never spoke of them. However, chatting with neighbours, on a bench, he, as if accidentally, would sometimes mention certain circumstances. His invalid pension was higher than that of his contemporaries who did not fight. My mother told me once how she convinced him to wear his medals on his jacket, for a 60th birthday photograph. We still have it. The photo comes out each year, on the anniversary of his birth, and on Victory Day, placed beside his fishing lamp and a lit candle.

On my mother’s 90th birthday, we invited a military orchestra to play for her, evoking the memory of her husband-front-line soldier. Maria Petrovna Cherkashina enjoyed those wartime melodies, harking back to youth. Gathering the whole family, we tell stories of his love for fishing, in the Severski Donets: the site of fierce fighting at the beginning of the war. His son and grandson are both now fishermen too, having learnt during summer holidays, with Mikhail. His love of fishing found expression in craft works, such as his making of a lamp in the shape of a boat (which includes a ‘stylised’ lantern replicating his father’s fishing lantern).

For the 70th anniversary of Victory, we’ve collected all our family ‘war relics’, including the medal ‘For Victory Over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945’ and the second ‘1st Degree Order of the Great Patriotic War’ (awarded to my father, alongside many other veterans, in 1985). There are various certificates, orders and medals, given in memory of veteran Mikhail Cherkashin.

On Victory Day, we talked about his uncompromising attitude towards those without honesty: thieves and timeservers. Like all of us, he had weaknesses and strengths. When he spoke, it was after consideration, and he never made empty promises. He would easily lend money, knowing others’ need and hunger. Often, he helped young musicians and newly-married couples on our street, Podgornaya.

When Yuri, my brother-trumpeter, had his daughter, my father rode his bicycle (his favourite form of transport) to take fresh soup to his daughter-in-law, Lyuba. He liked to watch football and hockey on TV, especially international matches: a love he imparted to me.

He also loved wind music. After playing at the May 1st celebrations, in Volchansk’s main square, he’d usually sit in the courtyard, under a grapevine, when it was warm, joining relatives, including my cousin Oleg, who was a pilot-navigator and son of Red Army Commander Ivan Lugovsky, who died. When my father was younger, he would cook a chicken on a campfire, alongside kasha porridge. However, he never drank more than two small glasses of vodka, even on holidays.

Recently, my husband counted how many ‘direct heirs’ my father has. There are ten of us, all living, and more certainly will be born in future. We are the result of him surviving that terrible war. I can only think about our veterans of the Great Patriotic War with gratitude and will never tire of offering my thanks to my father, for Victory!

I am very, very proud of you. I hope, he hears me.

By Valentina Cherkashina-Zhdanovich