Honoured Artist of Belarus Oksana Lesnaya, an actress at the Maxim Gorky National Academic Drama Theatre, celebrates her birthday by speculating on the importance of true acting partners in film-making and theatre staging

Вksana Lesnaya was playing in Noel Coward’s Private Lives, directed by Valentina Yerenkova, on her birthday. Speaking of why she chose this performance — rather than Tricks of Khanuma, by Avksenty Tsagareli, in which she shines as Kobato, who is a worthy rival to Khanuma (played by People’s Artist Olga Klebanovich) — she says, “Everything is simple. Private Lives is a light-hearted show, loved by audiences. Moreover, it’s short! With this in mind, I decided not to make my friends, relatives and colleagues wait too long for me after the show, to share their congratulations.”

Ms. Lesnaya is a talented actress who can hardly be ignored; she can perform all sorts of roles, having stage magnetism and charm. She draws everyone to her. I first noticed Ksyusha (as she is called by friends) at the Youth Theatre. She was playing the Butterfly in Thumbelina, carrying Thumbelina on a leaf. She was a wonderful, expressive butterfly, wearing shoes two sizes too large, which kept slipping from her feet, to the audience’s amusement. However, I was struck by something else: Butterfly Lesnaya was both lyrical and distinguished simultaneously. Her charm and humorous expressions couldn’t help but evoke laughter. Moreover, Oksana was irresistibly feminine. I remember thinking that it wouldn’t be long before she’d move on from the Youth Theatre, and I was right.

Ms. Lesnaya has been performing with the Russian Theatre since 1991, taking dozens of roles: Yevlampia in Ostrovsky’s Wolves and Sheep; Leda, the Queen of Sparta in Amphitryon (based on Greek mythology); Inken Peters in Before the Sunset, by Gerhart Hauptmann; Anna in Maxim Gorky’s Vassa; Nastasia Petrovna in Uncle’s Dream, by Fiodor Dostoevsky; and many other. In addition, she has taken various film roles.

In 2011 (Belarus magazine, #10), I wrote about Oksana diverse repertoire of roles, describing her as ‘a tightrope walker, teetering on the brink that separates one character from another’. I declared that she can, by turns, appear ‘unapproachable and proud or extremely tender and feminine’. I noted her power to be a vamp, a businesswoman, a beauty or a poetic, romantic villager, as in Zoska based on Yanka Kupala’s Broken Nest.

Speaking of her acting partner, she told me, “When performing Maryla, I was crying as I looked at Zoska-Lesnaya. I had the impression that Ksyusha was floating across the stage, being tragic and beyond tragedy at the same time.”

I feel the same today. Oksana seems to soar over the usual scope of a role, expanding its limitations, giving the lyrical a touch of comedy, so that it’s hard to know whether to cry or laugh. Her stage emotions change as quickly as they do in children. Her face is very impressive in such moments, with her inner world bared to all. She inspires a range of emotions in her audience and her characters stay with you long after you’ve left the theatre.

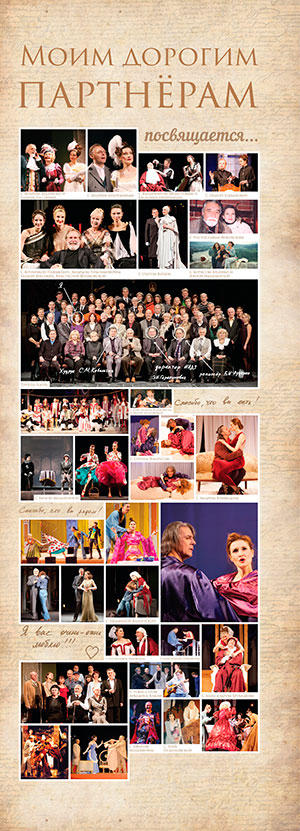

Her Amanda Prynne in Private Lives is wonderful, displaying the usual diversity of mood and alternating rhythms. Her beautiful voice, facial expressions and graceful movements are a joy to behold. After the show, she received a welcome address from the Ministry of Culture of Belarus, in addition to flowers. She was surrounded by smiling faces — of her mother and step-father, son and husband, friends, colleagues and her fans. The atmosphere was comfortable and warm, as is usual for the Russian Theatre. Moreover, the theatre is known for organising birthday parties for its actors, after a performance. At the celebrations, I asked Oksana what she’d like to share with us and she chose to talk about her acting partners.

|  |

She began, “I love my life and life in general. I love people and my acting profession. I like knowing that there’s still so much to learn; for example, I’m studying the role of Olivia in Twelfth Night, reading the script. I admire the accuracy of Igor Skripka’s translation. He has been guided by the comical nuances of the characters, keeping their expressive speeches.”

She admits, “I’m so pleased that Sergey Kovalchik, the theatre’s Artistic Director, has chosen me for this role. However, I don’t yet know what direction this ‘vessel’ is being guided upon by its ‘captain’. Shakespeare’s work is genius but resembles a modern Brazilian soap opera, about twins, or an Indian movie about Zita and Gita. We have to allow the theme to reign, although sets and costumes are important. Probably, we’ll premiere in July, opening the new theatrical season. Sergey Chekeres is playing Duke Orsino, having also been my partner in Intimate Comedy.”

She continues, stressing the importance of a good acting partner and the degree to which you rely upon each other on stage. “You may try to move along your own path but, if your partner doesn’t want to go with you in a particular direction, the performance will break down. On stage, if actors move in different directions, the emotional component of the play and its atmosphere are lost: ‘spat into eternity’ as Faina Ranevskaya used to say about photos. I wouldn’t enjoy acting in this way, or watching such a performance. I want to respond to my acting partner. Of course, they have their own character, but also play their role a little differently each day, depending on their mood, or degree of fatigue. I must take this into account, paying attention to what I see and feel. Either, I need to support them more, if they are tired, or shift my own performance, so that their tiredness appears justified. Otherwise, the acting can appear ‘mechanical’: simply reciting text.”

She asserts that we have to believe in the characters, gradually building a relationship with the audience through small gestures and speeches, as in the real life. We want to see a character transform through the performance as they learn something about themself.

“I like it when my partners make me change,” she explains. “In Wolves and Sheep, I partnered Rostislav Yankovsky and Vladimir Shelestov, who did this for me. Mr. Shelestov played Berkutov — a businessman and a thoughtful representative of the emerging merchant class, who courted my Yevlampia. I can’t even imagine anyone else playing opposite me. Volodya is a wonderful partner. As for Rostislav Yankovsky, I partnered him in Gerhard Hauptmann’s Before Sunset, Bernard Shaw’s Simpleton from Unexpected Islands and other shows. Each time, he was different.”

She continues, “The duty of an actor, in my opinion, is to love his partners, regardless of their condition or appearance. They might be sick and be on stage with a high temperature, so that they can’t act as they would usually. In this situation, you’re obliged to help. If they can’t demonstrate all their skills for some reason, then you take on part of their ‘burden’, taking on more of the emotional journey yourself. This is the style of partnership which enriches me. True partners are communicating vessels. You pour into one but both are filled equally. This principle is vital among stage actors. If actors ignore it, nothing good can happen. We take this approach sometimes with novices, when they have to take the lead and speak a significant monologue. The more experienced actor helps engage with them, so that they don’t feel overwhelmed. However, they can also punish young actors by talking quietly behind them, causing the novice to look back. It’s a particular teaching method.”

“All my acting partners have been mostly responsible. I remember once flying back from shooting in Khanty-Mansiysk, where it was minus twenty degrees. Back home, we had twelve degrees above zero and, probably due to this difference in temperatures, something happened to my voice. I was unable to speak during the day but, after an injection in the evening, I recovered. However, my ‘new’ voice was much deeper. I had to cry in the performance, which was full of love, blood and hot passion. It was impossible for me to perform with that voice. I was acting opposite Sergey Zhuravel, who took over responsibility for all the emotional scenes. It was a great part of my job.”

Oksana tells us, “I was taught lessons in partnership at the Russian Theatre: by Rostislav Yankovsky and Alexandra Klimova. I was told, gently, that, as soon as a scene starts to fail, the audience stops listening. Rather than trying to seize the hall as your ally, you have to draw closer to your partner. This will bring the audience back to you, being eager to see what’s happening between these two people. If two people are interested in each other, the audience becomes interested in them as well.”

Anna Malankina (Ninochka) and Sergey Chekeres (Leon) play with Oksana in Melchior Lengyel’s Ninochka. She plays Duchess Ksenia, who loses her lover, Leon, to Ninochka. Oksana explains, “In the final scene, I offer Anna money and family jewels on the condition that she leaves without telling Leon. Essentially, Ksenia buys Leon but Ninochka agrees in the belief that, as a Bolshevik, she will be able to regain his heart at some later time. Every performance, this scene haunts me. It can subtle and lyrical, with Anna-Ninochka dissolving in love, suffering yet forced to accept my suggestion. At other times, she appears as a tough Bolshevik, choosing money over love. It depends on how the show is played from the beginning up until this scene.”

Oksana admits that actors sometimes surprise their directors in rehearsals, discovering new subtleties hardly prescribed in the play and creating a completely different atmosphere. “I felt this in Patrick Marber’s Touch, which is about lost love and confusion. We played the scene with desperate grief for our loss and shouted dreadful words at each other. The audience would fall completely silent, truly taking on board our characters’ despair. They understood that it’s sometimes impossible not to swear terribly, because there is too much pain. When an actor becomes experienced, he grows through his partner. If he proceeds alone, it’s like an instrument out of tune with the others,” she tells us.

“I’m currently enjoying partnering experienced Olga Klebanovich in Tricks of Khanuma. We have a fight scene in which we circle each other. At first, I was afraid that she wouldn’t be able to move quickly enough, removing her bag and coat, and that the audience would lose interest but there was no need for me to worry. Olga always manages to meet her mark. She is one of those partners who get under your skin. You are separate individuals but she has the power to command you, drawing you out. With Olga, I feel free to act in different ways, because she always picks up the baton, stretching her line, enriching it and aiding me. It’s like playing doubles tennis. It’s the same sort of partnership, whereby one supports the other. We hear each other, listening not to ourselves but to those around us.”

Speaking of partnership, Oksana’s Evening of Jewish Jokes has become an exemplary performance, hosted on the Yanka Kupala Theatre’s small stage, where actors share space more intimately. She notes that even the smallest technical errors cannot be hidden, requiring the cast to support one another more than ever. Office is another performance relying on the actors working closely, as is Wedding. Oksana praises the cast’s ability to work in harmony, without anyone trying to steal the limelight.

She likens the partnership on stage and in film, noting that a good cinema partner stays around until all your scenes are finished. She recalls filming with Vladimir Steklov, playing a museum worker who was consulting Mr. Steklov’s character on the discovery of a crucifix. She tells us, “I had a long and boring monologue about the exhibit. Mr. Steklov, sitting behind the camera, listened to me carefully and — to revitalise my boring face — began grimacing. As a result, a certain element of coquetry appeared not envisaged by the script. I began to come alive. He treated me as a woman rather than as a museum employee. If he’d just gone, I’d have been talking to the camera alone. The greater the actors are, the more professional they are, always remaining such while their partners continue filming.”

Performances usually remain ‘alive’ for a certain period of time, a year or two, before they grow tired. The play becomes routine, losing its sparkle. If it is to continue, it needs to be stirred up. It’s a real challenge. Oksana reveals, “When I began acting in Before the Sunset, Rostislav Yankovsky and I decided to play a game, giving each other chocolate before each show, as a gesture of ‘good luck’. We had to keep thinking of ‘new’ varieties of chocolate, which was inspiring (and entertained us). We knew that our boats would rise or fall together and that we needed to keep fuelling each other. It’s lovely to arrive at the theatre and see the confectionary that your partner has left for you. You enter the stage in a certain mood. I appreciate such ‘behind the scenes’ relationships very much.”

Oksana compares her relationship with her theatre colleagues, in terms of her feelings, as being akin to that with her family. “If I quarrel with one of my relatives, they don’t stop being part of my family. Deep inside, I still treat them warmly as I understand that they have the same professional challenges as I do and that they have the right to make mistakes. I’m no saint but my inner sense of kinship with colleagues allows me to ignore some moments, accepting them as they are. We are equal, despite titles or regalia. When we remove these, we are all simple people, with our own fates, but perfectly pleasant. I prefer to put any negative feelings away in my pocket, with the hope that there is a hole through which they’ll be lost. My positive feelings go into another pocket, for safekeeping.”

By Valentina Zhdanovich