By Viktor Mikhailov

From the beginning of the 20th century, many Belarus cities, especially Vitebsk and Minsk, served as an original testing ground for art, avant-garde art schools remained here for a long time. And, like one century ago, today’s domestic art is notable for its variety of experimental forms, absence of similarity, unilaterality and simplicity.

Nowadays, one cannot surprise anybody with avant-garde in fine art. Moreover, many young artists even abuse their not very distinct adherence to this style. Another matter is when you view avant-garde experiments in painting or in graphics of almost half a century ago. However, somewhere during the 1980s-1990s, Belarusian avant-garde becomes an open alternative to official art, when it ceased to be an underground movement.

Basically, artists of informal direction aspired to re-establish the discontinued connection with classical avant-garde of the early 20th century. In the environment of informal art there arose original forms of artistic activity: action art, performance, video-art, declaration, manifestos, installations and many others. In the 1980s, informal exhibitions were already held in the many different places: in cinema foyers, libraries or assembly halls of various public institutions. Such exhibitions as Art Studio, Fragment-Event ’87, On Collector’s, Prospect and Panorama in the 80s were a real manifesto of free art.

Inside the artistic process of informal art there were notable groups of creatively close artists united by a uniform vision. At this time, there was an organised association of creative intelligentsia, such associations as Form, Galsha, Plyuraliz, BLO, Vitebsk Square, 4-63 from Polotsk and many others. Each group of artists offered their own manifesto as an alternative to generally acknowledged professional art. Here is the example of the text prepared to the exhibition of the Form association. ‘What undoubtedly unites all artists is the conviction that the development of art is largely a development of form, hence the name of the association, which also was a reaction to that long-term struggle of dogmatic art with the so-called ‘formalism’’.

And here is the extract from the booklet of 1989 of the Panorama exhibition, where artists of 9 informal associations were exhibited. ‘...Belarusian fund of culture was guided by the purpose to show the cut of modern Belarusian art of nonconventional directions: expressionism, surrealism, conceptualism, pop art, installations, etc. Modern art came to modernism in search of new figurative means... There are no bad or good directions in art, there are only bad or good artists. Avant-garde is needed as well as any other direction in art, to any society which considers itself to be developed culturally and economically’.

The creative association ‘Square’ was organised in 1987 in Vitebsk. Its task included the establishment of aesthetic principles of classical avant-garde and postmodernism in the artistic life of the Republic. The association became the environment for individual creative processes focused on certain aesthetic values. The work of the association was organised in the form of actions and exhibitions. The first such action was the exhibition Experiment in 1988, devoted to Kazimir Malevich’s 110th anniversary, where, apart from the work of artists, information about Malevich was also shown and introduced.

Soon after, in the structure of the Belarusian Union of Artists, there started to appear sections based, not on forms of art (painting, graphics, sculpture), as earlier, but on interests or ideological principles. Nemiga-17, an association of adherents of pictorial and formal beginning in art appeared. From the catalogue of 1988 of exhibition Nemiga-17 — ‘Artists deny the understanding of art as illustrations of political slogans. Art cannot and should not fall to the role of commentator of the already ideologically comprehended. It should take a person to the comprehension of new public needs, to form a new tomorrow’s style of life’.

At last, participants of the Nemiga-17 group understood individuality in art not as selfish, free self-expression. According to them, individuality, as well as in all spheres of life, is a way of definition, a way of creation and development of public need.

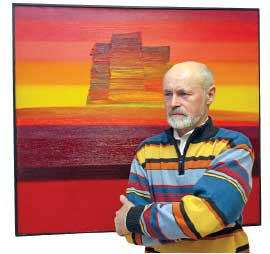

Seeing the works of artists of Nemiga, you come to the understanding that they are true masters. Strong and mature. They are individuals — everyone in their own world of creative aspirations. And with all that, there is a certain community of spirit between them. Today, they are already about sixty years old, and some are even older. In general, I think, they are happy people. They are free to work in art as they like. There is no administration over them, no ‘social order’, no fashion thought up by someone else. However, having met them much earlier, you note that their way to this freedom was long and difficult.

Today, they are already about sixty years old, and some are even older. In general, I think, they are happy people. They are free to work in art as they like. There is no administration over them, no ‘social order’, no fashion thought up by someone else. However, having met them much earlier, you note that their way to this freedom was long and difficult.

Nemiga is from the generation which is known as ‘the Seventiers’ (cultural figures of the 70s). The psychological dissimilarity between them and leaders of art of the 1960s is natural. Circumstances deepened this difference and led to mutual rejection. Younger workers were not attracted by the social and political character of creativity of ‘the Sixtiers’, mainly due to the literary character of their figurativeness, and absence of original interest in updating of the language fraught with the loss of quality of flexible statements. Avoiding creative dialogue, the senior preferred long-term tactics, and the consecutive ousting of the young from the public life of art. The young, certainly, did not want to accept the position of marginal people. A chance to protect their status in culture was given to them by the idea which generated the Nemiga association. The idea was national-romantic by nature. It contained stimulus and a basis for original picturesque searches, being fully armed with a professional fine arts school, to address anew, the poetics of Belarusian folklore, national creativity and peasant crafts.

Such a movement preserved all completeness of topicality for Belarus. The rise of the national school in the 60s had its own features. Unlike, say, Ukraine and Moldova, new trends in art of the Republic were basically nourished, not by centuries-old folklore heritage, but by the tragic memory of a war-time past. Therefore, music of the white colour, peasant weaving, ornaments and other plastic motives, characteristic for embroidery, traditional items from clay and wood, the blinking gold of Belarusian straw were so attractive for fine art of the 80s. These were the expressive symbols of folklore thinking in all their riches. Moscow ‘Seventiers’ at that time spoke about the development of a ‘world museum’, about the ‘carnival’ tonality of the perception of life. However, their associates in Minsk were more likely interested in other things. It is possible to call it an attempt of national identification. It is necessary to remember that the developing group included not only Belarusians; there were also newcomers from different corners of the former USSR, up to Siberia and the Far East. Nemiga, taking its name from the times of the Tale of Igor`s Campaign, is a small river under one of the central quarters of modern Minsk, where the house with workshops of artists appeared not so long ago, was perceived as a historical, geographical and cultural symbol, and the participants of the exhibitions with the same name, connected their creative thoughts with this symbol. As if listening to the stream of time, they dreamt of picturesque visions of rural childhood, folklore legends depicted in pictures-songs, pictures-parables. These were pictures without narrative about touching rural lovers, without jokes with which the quarrelsome Moscow primitives amused the public. As a rule, the plot was delicately visible through paint. After all, the purpose of the authors was also comprehension of themselves, self-determination in colour, rhythm, movement of space and the breath of picturesque mass. In Minsk, there might appear the style of picturesque poetics painted, certainly, in colours of that place and time.

As if listening to the stream of time, they dreamt of picturesque visions of rural childhood, folklore legends depicted in pictures-songs, pictures-parables. These were pictures without narrative about touching rural lovers, without jokes with which the quarrelsome Moscow primitives amused the public. As a rule, the plot was delicately visible through paint. After all, the purpose of the authors was also comprehension of themselves, self-determination in colour, rhythm, movement of space and the breath of picturesque mass. In Minsk, there might appear the style of picturesque poetics painted, certainly, in colours of that place and time.

However that was, probably a possible but too idyllic option. Reality resolved everything differently. It happened that during the decline of Belarusian artistic life of the Soviet time-period, the movement of Zoya Litvinova, Galina Gorovaya and Tamara Sokolova, Nikolay Bushchik and Anatoly Kuzne-tsov with Sergey Kiryushchenko were not understood; neither in their environment, nor among their cultural chiefs. On the contrary, that field, where they hoped to grow shoots, started to sprout weeds. Souvenir mass-produced items in painting, gorgeous life of fashionable salons, rushed to exhibitions, with their importunate diversity, defining the style of appearing independence.

Idealists of Nemiga could do only one thing — to move in any other direction. Their new choice should become and appear critically difficult, all the more so that behind their shoulder was more than a decade of devout professional works. The choice was difficult for any gifted artist in the Post-Soviet reality both in Moscow, in Minsk, in neighbouring Vilnius and in St. Petersburg. Everything that to the middle of life appeared better or worse constructed, everything that gave at least relative creative stability, fell apart at the seams. The collapse of the Soviet system left to the Seventiers almost no choice, proceeding from the priorities which existed within the limits of foreign and domestic conjuncture or, easier, solvent demand for their creative efforts.

Oh, it does not mean at all that they kept away from the human, lost responsiveness to the life of people or ability to hear and excite many of us, to find support and to cause response in an organism of living culture. However they approached the process of creativity as artists-openers. They tried to introduce something essential, something that they predicted, something that was for us still meaningless, unexpected and not seen. Nikolay Bushchik, perhaps, did not leave the world of his early landscapes, symbolical sacraments of nature and appearing in planetary harmony. However, his pure, shining colour accords gave an impression as if terrestrial elements merged with blazing spiritual space. Galina Gorovaya is a true sculptor, capable of finding out the latent soul of wood, stone or metal. The love feeling of intimate contact of two human beings in her creativity can be close to penetration into the dumb world of animals or birds, with a unique sensation of the character of the strangest characters of life surrounding us. With pride, delight and tenderness, she is able to admire the beauty of the phenomena of life, intensifying this beauty in plastic compositions using colour accents of remarkable brightness coming from a national perception and freshness unusual for tired eyes. Thus here appeared a special mythology of a master, which united the small and the great into a single circle, an animal and a human in their unique originality.

Nikolay Bushchik, perhaps, did not leave the world of his early landscapes, symbolical sacraments of nature and appearing in planetary harmony. However, his pure, shining colour accords gave an impression as if terrestrial elements merged with blazing spiritual space. Galina Gorovaya is a true sculptor, capable of finding out the latent soul of wood, stone or metal. The love feeling of intimate contact of two human beings in her creativity can be close to penetration into the dumb world of animals or birds, with a unique sensation of the character of the strangest characters of life surrounding us. With pride, delight and tenderness, she is able to admire the beauty of the phenomena of life, intensifying this beauty in plastic compositions using colour accents of remarkable brightness coming from a national perception and freshness unusual for tired eyes. Thus here appeared a special mythology of a master, which united the small and the great into a single circle, an animal and a human in their unique originality.

Another two participants of the group — Anatoly Kuznetsov and Leonid Khobotov — chose abstract methods. But, again, in their searches, they are quite original. In general, the meaning of abstract-symbolical images can be felt in some extent, but it is almost hopeless to try to describe it because everything is based here on very unsteady and subjective associations which run and vibrate depending on our mood. It seems that Kuznetsov is attracted by big spaces, with various forces of nature in which a human tries to distinguish the music of their own heart, their own lyrical conditions, the blinking of a morning landscape and the exciting influx of form-creative will. And all these can be found in a wind gust, the blazing of colour in lightning, splashes, sunbeams, and at times, in the methodical and laborious work of control over these elements using the picturesque surface of canvas. The abstractions of Kuznetsov seem like a metaphor for the life of the artist, his imagination in a duel of a brush with inconstancy of infinity behind the walls of his workshop. Leonid Khobotov is like an architect of natural essence.

Mentally pulling together similar observations, one wants to speak about the certain philosophy of the world outlook of the masters of Nemiga. They had to live during the time of the next collapse of the country, fortunately, not such a catastrophe as in the former days of revolution and two world wars. And that reliance which they found for themselves, hoping for the future, was a reliance on the creative elements of nature, healthy bases of the eternal way of human life — everyone after their own fashion. They do not tell naive fables, they charge and inspire their spectators with terrestrial first-born force. And in this work, I think, is the highest power and wisdom of Zoya Litvinova’s creativity, the most mature master of Nemiga association.

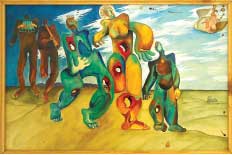

The artist of rare temperament, initially inclined to plans of big scope, Litvinova completely passed the way of spontaneous ardour for the pagan force of life. Her canvases, which often glorified scenes of national festivities, gained wide popularity even in the Soviet years. She also worked as a monumentalist, most likely gobelins with peasant motives of the 80s-90s became, for her, access to a new understanding of the human being of the earth. Gradually, however, in a game of vital forces of nature Zoya Litvinova started to see the higher religious sense. She started thinking about the infinite complexity, the contradictory variety of the world order, and also about the sincere-moral being of the human being. Even today, Zoya Litvinova does not change her favourite motives of ritual dance which came to European art at the new time from Matisse, Picasso, Goncharova.

In these, her reflexions, the artist at last reached the mysticism of Christianity. She reached the secret of belief, love and sacrificial death, symbolics of all that’s real on the earth. Here again, we approach one of the intimate details of the artistic language of Zoya Litvinova. In scenes of not only holidays, but also passions, often telling about the most difficult moral and philosophical collisions of the history of mankind, she sheds soft golden light on depicted figures. Perhaps, it is the light of belief and her love of people, it is that high, clear lyricism with which symbolical Nemiga warms her and her associates. The history of generations of ancestors took place on Nemiga’s banks. In general, the creativity of these artists exists in the space of modernist traditions in art. Horizons of their way can be defined by following words: form, expression and spirituality.

In general, the creativity of these artists exists in the space of modernist traditions in art. Horizons of their way can be defined by following words: form, expression and spirituality.

Unlike Litvinova, almost all other participants of association work today in the space of abstract art, thus preserving strong ties with reality — the main source of impressions and creative impulses. Abandonment of figuration was in many respects natural, caused by the logic of the evolution of their thinking, a desire to escape from literariness which was alien to the nature of fine art. They aspire to embody their idea concerning the world picture, using, first of all, internal figurative-flexible resources of painting and sculpture.

Certainly, each artist had their own stimulating motives and their own way to the given decision. Nikolay Bushchik, in early figurative works, unlike his other colleagues, focused more on the problem of national-cultural identity of own creativity, on visual concreteness of this or that everyday plot or landscape motive. In the artist’s pictures of the last years it is possible to note an aspiration to the expansion of horizons of vision and themes of supranational character, which today are of vital importance for him, to the comprehension of oneself and one’s own creativity in the context of universal values, and, hence, to the search of other figurativeness and other languages. According to Bushchik, the abstract form helped him to get free, gave him not only freedom of expression, but also took him to a new level of solidity of artistic expression.

However, the painting of Anatoly Kuznesov is more impulsive and improvisational. He was one of the first in Nemiga who came to abstraction and decided on own his working methods with sensual-malleable material. However, Kuznetsov prefers to call his painting, not abstract, but non-figurative, noting its sensual basis (in his opinion, abstract art assumes the presence of certain intentionally verified concepts, while this is absolutely alien to his creative nature).

Certainly, with its impulsive spontaneity, the painting of Kuznetsov also contains certain organising moments, uniting key-notes. However both the forming of the correlation of colour spots and the search of the rhythmics of movement of ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’ surfaces, spatial moves, and surface game are carried out exclusively at a meditative level. The artist intuitively shows such a quality of his creative consciousness, as the creation of beauty to which, in general, he never aspired purposefully, but which he values as the equivalent of the highest harmony which has not lost a deep sense and urgency for him today.

Strange things happen today in the world of art. Political technologies more actively penetrate into its territory, watering down the borders of art and transforming it into a documentation of those or other phenomena and events of life, while an artist turns into a publicist, politician, sociologist who is less interested in questions of aesthetics. Problems of form and beauty are moved to the background, giving way to pseudo-social pathos of reasoning about the processes of the present moment.

As we see, artists of Nemiga are again not in the movement with their search for the eternal or momentary values and truths, both in art and in life. But they are not worried about all that any more. And not because of powerlessness, after all, to go against the stream, keeping a balance of sincere and physical strengths is much more difficult and more dangerous, than simply to yield to this stream. Before us, are very strong people with their own positions, who understand the aсt of art as an individual activity in the world order as an individual responsibility. This tendency is already more distinctly seen in the modern world artistic process and, probably, from these positions, there will appear new directions and new main ideas. The further ways of the artists of Nemiga are outlined in the light of this tendency.

Here is how the already known Belarusian artist, Nikolay Bushchik, explains his participation in the Nemiga-17 association today, with of his early works is represented at the exhibition in the Museum of Modern Fine Art. “At those times, in the 80s, art passed towards excitement. It started to offer themes of worries, themes of the emotional perception of objects. In that way, as you feel them or want to turn them into any feeling. To make something dark blue into red, and to select other unusual colours nearby. And together it will create either a dramatic situation, or a situation of lyricism, or a situation of enthusiastic feeling. This lead to a change of tasks and approach in art from the 10s–20s of the 20th century. Let’s take the creativity of Petrov-Vodkin, suprematists with Malevich, artists of the 30s, Konchalovsky. I take close art, without mentioning Europe. And there were Matisse and van Gogh who worked adequately with their impressions and images. Certainly, art became more flexible, artists began to search for styles which would create a mood. And now, an artist searches by using rhythm, light-stress for such conditions on canvas which force to worry. Certainly, much happens at the level of the sub consciousness, associativity, as from the most visible an artist chooses the most active and characteristic, that expresses feeling or emotion. And spectators understand and reach for such fine art. They say ‘This is really similar’. Together with the artists’, their creative imagination also starts to play. It gives them more pleasure, than simply to look at any concrete accurate object or real landscape. Hence it is absolutely another direction in fine art, where art starts to get style. Each artist develops his or her own style which helps to create space in the way he or she sees and understands it. This is the difference between artists.” How would you describe your style?

How would you describe your style?

“Certainly, I can describe myself, although art critics will give a more capacious description or perhaps, an art fan. In my work I aspire to that, which, as a result, creates a sensation of pleasure and harmonised rest, the mood bringing a person into good, vital harmony.”

Nikolay Bushchik has not changed in creativity over the course of time. Here is how he formulates his modern creative credo. “It seems to me, that artists have now divided into two directions in creativity. Some of them work for black, and others, for light. I work for light. I am interested what my motherland is, in its fine Divine creation. All the bad, bad moods, bad actions we make ourselves. All our displeasure results only from the discrepancy of our desires to what happens, and that’s all. What for? Who needs this? Everyone should manage themselves, and the blackness inside. In creativity, I would like to confirm beauty, harmony, the cleanliness of morning and evening, the creation of a summer downpour or a fine winter snowfall. When I manage to achieve this, it grasps me more.”

They are different, these elders of Belarusian avant-garde. They express thoughts and sensations differently in their works. They are individuals, and this creates an interest in them.

Such a phenomenon as ‘artistic community’, rich on formal and figurative searches and experiments, is felt strongly in Belarusian art. Artistic avant-garde revealed itself in painting, architecture, design, music, theatre and cinema. It influenced the whole style of life of the 20th century. The comprehension of art and culture of Belarus in its avant-garde displays remains topical even today, in the 21st century, as an understanding of sources of modern culture.

The Minsk Museum of Modern Fine Art recently held an exhibition which visually illustrated sources of Belarusian avant-garde. The uniqueness of this project was that, for the first time, the works were sequentially and fully gathered in a uniform exposition ‘One Hundred Years of Belarusian Avant-garde’. Based on various collections, both private and State, the project fixed the variety of art. It was an original attempt to build a chronology, to introduce avant-garde associations and to interpret concepts of avant-garde as integral part of Belarusian art.